It is a little known fact that in the annals of the British Museum there is an incredible collection of timepieces and horological artefacts in the ‘Reserve Collection’. The impressive horological collection held by the Museum today is predominantly thanks to the generosity of benefactors and horological collectors.

The first person to actively promote the relationship between collectors and the Museum was Sir Augustus Wollaston Franks, who joined the Museum staff in 1851. Franks was an enthusiastic collector himself, and donated over 22,000 items to the Museum. Of these, 103 were horological items, with a small number of clocks and 13 watches. Perhaps his greatest contribution to the horological collection was in encouraging leading collectors of the time to contribute to the Museum’s collection.

One of the greatest horological collectors of the twentieth century, Courtenay Adrian Ilbert, (1888–1956) has had an enormous impact on the Museum’s horological collection. In 1958 the Museum was able to acquire Ilbert’s entire collection.

We spent a wonderful afternoon in the Museum’s ‘Horological Student’s Room’ with Paul Buck, Curator, Horological Collections, Horology, who took us on a marvellous horological journey through an amazing collection of watches from the late 16th century to the 19th century.

Paul explained that the ‘Study Room’ catered for around 400 visitors per year, ranging from ‘Clock Clubs’ to academic institutions, i.e. the Birmingham School of Jewellery and covered all aspects of horology.

Introducing the watches he said that when watches first started being made, ‘showing off’ was a large part of their function- whether it was the maker demonstrating how clever they were – or those who commissioned/bought the watch as a sign of their wealth and status. It was to a large extent about keeping up with ‘fashion’ and having access to the ‘latest technology’, even as far back as the 1590’s.

We start our journey in 1500’s when the first spring driven watches first appeared. They were terrible timekeepers but nonetheless important status symbols. The first watch we get to see ‘up close and personal’, was from Nuremberg made in 1540. Sadly the movement is long gone, but it is beautifully engraved, has a built-in sundial and a moon phase ‘complication’.

We move swiftly on to 1572, the date of the St. Bartholomew’s Day massacre. This was an appalling event, but it was significant for the advancement of horology as it resulted in an influx of Huguenots (French Calvinist Protestants), many of whom were highly skilled craftsmen and watch makers.

Moving forward to 1610-20, there was a trend for watches to be smaller and of a similar design as demonstrated by two watches, one by Robert Grinkin The Elder, a London maker and Richard Barnes from Worcester.

Next is a super alarm watch by Cornelius Mellin who was listed in the 1622 petition of the London clockmakers that was instrumental in forming the Worshipful Company of Clockmakers (in 1631) as living in Blackfriars with a group of apprentices and journeymen.

We then get to see some interesting ‘Form Watches’, made between 1635-50. The three examples are in the shape of a ‘Skull’, ‘Pear Drop’ (Amber) and ‘Tulip’ (Rock Crystal).

We have ‘history in our hands’ when we come to the next watch made between 1630-40 – a ‘Puritan Watch’ as it is known – by John Midnall. Some believe this watch was once owned by Oliver Cromwell (albeit doubtful – but we can only but dream!). Made of silver, it certainly is functional! It has ‘OC’ engraved on one side of a ‘fob’ and a ‘coat of arms’ on the reverse.

We are treated to an exquisite enamel watch made by Dutch maker in about 1650, signed Isaac Pluvier Londini. It is as bright today as it would have been 350-years ago. It really was fabulous to see the detail of this beautiful timepiece – whoever bought this was really showing off!

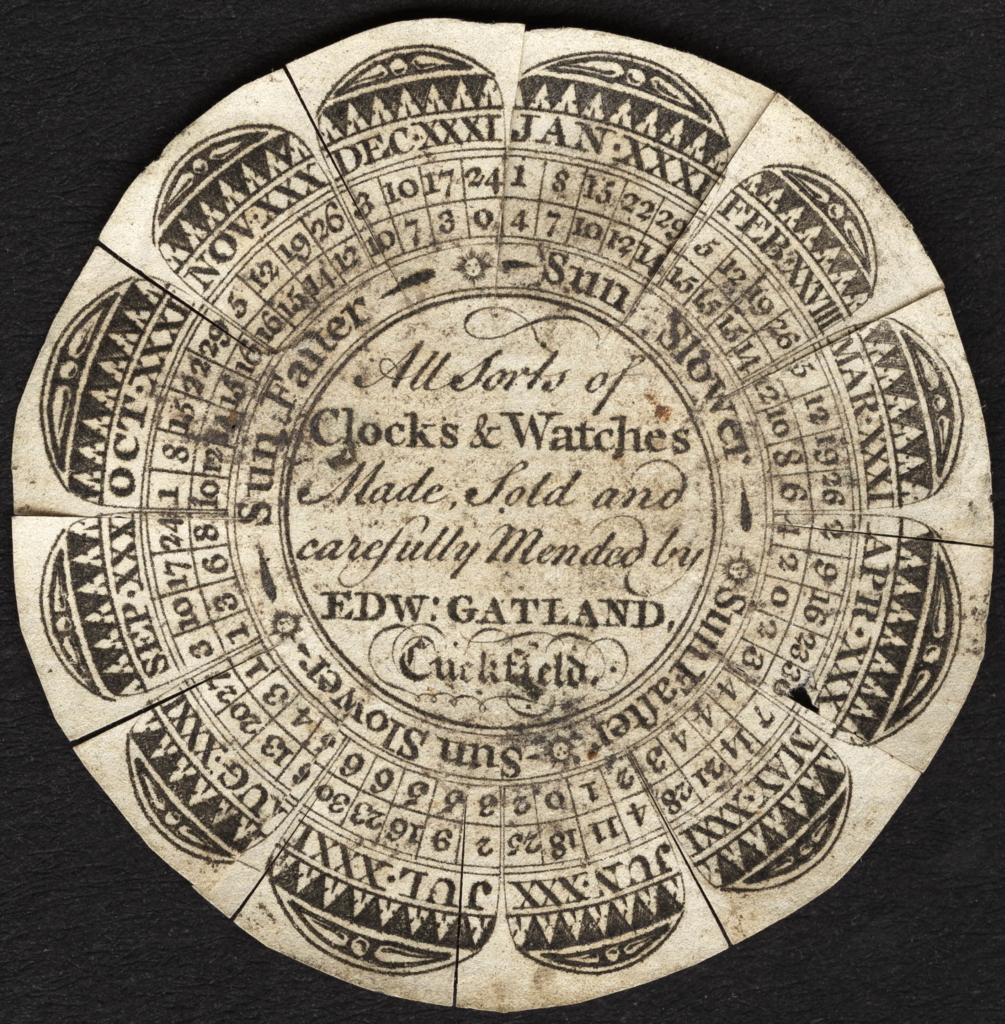

We were moving swiftly into the mid-17th century and a time when there was a real emphasis on intricate work, with many examples of filigree work and super decoration. The next three watches made between 1655-65 we see are a fine filigree watch by Benjamin Hill, a pair cased example from Robert Acastle, Taunton and superbly decorated watch by eminent maker, Richard Riccord that includes a watch paper with an ‘equation’ table to calculate the difference between solar and mean time.

Next we see a watch that was found in the River Thames by Custom House Quay made in 1665. This is where your imagination can run wild. It was made by John Cooke (London) and shows the time as 9.20 – is this the time it stopped when it hit the water? Was the owner slightly ‘worse for wear’, having drunk too much Gin? Did its owner end up in the Thames to get away from the ‘Great Fire’ [of London]?

A chain and winding key belonging to the watch was also found nearby – the chain had lost its ring that connected it to the watch!

So we move forward to 1675, and the arrival of the balance spring and much more accurate timepieces. We get to see a fine gold, quarter repeating watch no. 117 from 1694 made by perhaps the most famous maker of all, Thomas Tompion, known simply as the ‘Father of English Clock-making’. This is when Tompion was in his absolute prime – and it really does show.

This period saw the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes (1685) which had a significant impact on watchmaking across Europe. Perhaps as a result of increased competition it coincided with a trend towards the creation of ‘novelty’ timepieces. A good example being the next watch made by Joseph Windmills of London in 1695, a ‘Wandering-Hour’ watch.

We then see the first example of a ‘world time’ watch made by John Neale in c.1750. It features 11 different time zones, including Russia and a semi mythical place called the ‘Strait of Anian’.

Now we can really get ‘carried away’ with the next watch that was made by the eminent maker, John Arnold in 1775. It was almost definitely used on Captain James Cook’s historic third voyage in 1776 to search for the North West Passage. This genuinely was ‘history in your hands’ – amazing to think about the journey this watch had been on and how it had survived looking so pristine.

Now we are entering the [crazy] decimal time of the French Revolution in 1789. It only lasted for 10-years, so there are very few examples of ‘decimal timepieces’ but we were fortunate to be able to see a fine example up close.

Keeping the ‘crazy’ theme, we then saw a watch made by Edward Massey in 1813 that had a ‘maritime’ theme. It was a ‘Stop-watch’ for four hours with two subsidiary seconds dials, one moving in 2.5 second intervals and was used to measure the distances between ships.

The final watch we saw was a watch by Ingersoll made in 1890 with a sham winding button. The pocket watch appeared to have key-less winding, but that didn’t actually work and the watch needed to be wound using an internal winder accessed by opening the back of the watch. Interesting given the current issues around authenticity.

We had a thoroughly enjoyable time with Paul, who made our fascinating journey through time, interesting, informative, engaging and above all enjoyable.

If you’d like to find out more about the Horology Student’s Room, please visit here

About Paul Buck

Paul Buck is the Curator, Horological Collections, Horology at the British Museum. He studied clock and watch making at Hackney Technical College, East London between 1992 and 1994 gaining The Horological Federation prize in 1992 and The ETA Course prize in 1994. He became a horological museum assistant in 1994 and later in 2006 a horological curator.

Paul is responsible for about 7,000 objects, including 1,000 clocks, 4,500 watches and other horological material. He also assists with the running of the Horological Study Room and its library.

All images are with kind permission from © The Trustees of the British Museum. Shared under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) licence

1 thought on “MrWatchMaster Visits: The British Museum – Time In Reserve”

Comments are closed.