In this occasional series, we will explore the life and achievements of the greatest and most respected horologists of their time. This feature will focus on John Arnold one of the most important horological figures in the pursuit of precision timing.

In the prolonged struggle to master longitude at sea, history often crowns John Harrison as the solitary genius who cracked the problem. His marine chronometers were revolutionary, and rightly celebrated. Yet revolutions do not sustain themselves. They must be refined, replicated, and made practical for the wider world. That task fell to another towering figure of eighteenth-century horology, John Arnold.

Arnold did not invent the marine chronometer, but he transformed it from a brilliant solution into a viable technology. Where Harrison proved it could be done, Arnold showed that it could be done reliably, repeatedly, and at scale – a contribution no less vital to navigation, commerce, and empire. In essence, Harrison’s chronometer was too expensive to replicate.

This is the earliest recorded and surviving pocket watch by Arnold with his pivoted detent escapement. The s-balance is a slightly later addition, being of the type employed by Arnold from 1779-82.

From Provincial Origins to Royal Notice

Born in 1736 in Bodmin, Cornwall, John Arnold’s early life offered little hint of his future importance. Largely self-taught, he arrived in London with ambition, mechanical talent, and a willingness to challenge established practice. His early reputation was cemented when he produced an exceptionally small repeating watch, which caught the attention of King George III. Royal patronage followed, giving Arnold both credibility and access to the scientific elite.

Crucially, this placed him in the orbit of the Board of Longitude, the same body that had scrutinised and, at times, tormented John Harrison. By the time Arnold entered the scene, Harrison’s H4 sea watch had already demonstrated unprecedented accuracy. But it was complex, idiosyncratic, and devilishly difficult to reproduce. The problem of longitude had been solved in principle, but not yet solved in practice.

Standing on Harrison’s Shoulders

Arnold approached Harrison’s work not with rivalry, but with a craftsman’s eye for simplification. He recognised that navigation demanded instruments that were not only accurate, but robust, serviceable, and manufacturable by skilled hands beyond a single genius.

While Harrison relied on bespoke mechanisms and intricate compensations, Arnold pursued elegant minimalism. He believed precision came not from complexity, but from consistency. This philosophy guided his most important contributions:

- The detent escapement (below – often called the Arnold escapement in its early form), which reduced friction and improved timekeeping stability.

- Simplified balance and spring systems, optimised for temperature variation and shock.

- Standardised construction methods, allowing chronometers to be produced in greater numbers without sacrificing accuracy.

Arnold’s chronometers (above) proved themselves at sea, performing reliably on long voyages to the West Indies and beyond. They demonstrated that Harrison’s concept could be translated into a practical naval instrument—a critical turning point for the Royal Navy.

The Craftsman as Collaborator

One of Arnold’s most enduring legacies lies not only in what he made, but in whom he influenced. His workshop became a training ground for the next generation of chronometer makers. Among them was Thomas Earnshaw, who would later refine the spring detent escapement into its classic form. Although the Arnold–Earnshaw relationship ended in rivalry and legal dispute, their combined work defined the chronometer for decades.

This transmission of knowledge marked a fundamental shift. Precision timekeeping was no longer the guarded secret of one man; it was becoming a discipline, with shared techniques, tolerances, and expectations. Arnold helped professionalise horology at the highest level.

When the great Abraham Louis Breguet visited London in the 1780s, he was introduced to John Arnold. The mutual respect between these two inventive horologists was clear. Arnold sent his son, John Roger, to work with Breguet at the Quai de l’Horloge in Paris from 1792 to 1794. In return, Breguet’s son, Louis-Antoine, came to London to work with John Arnold. Their friendship continued after Arnold’s death in 1799 through his son and successor.

This pocket chronometer, no. 11 (above) by John Arnold was made in London around 1774 and it has been suggested that John Roger Arnold probably took the piece with him to Paris, perhaps as a gift for Breguet from his father. The inscription translation reads: The first tourbillon regulator by Breguet incorporated in one of the first works of Arnold. Breguet’s homage to the revered memory of Arnold. Presented to his son in the year 1808.

Redefining Precision

Arnold was also a tireless advocate for measurement and testing. He understood that claims of accuracy meant little without verification. His chronometers were subjected to rigorous trials, and he welcomed comparison—not only with Harrison’s designs, but with his own earlier work. This iterative mindset was distinctly modern.

The chronometer above is one of a small group of his products signed ‘John Arnold No 1’. Arnold probably upgraded the movement more than once, fitting it with a spring detent escapement and two-arm compensation balance.

In doing so, Arnold helped change how precision itself was understood. Accuracy was no longer a marvel to be admired; it was a performance standard to be met, logged, and improved. That mindset underpins modern engineering as much as it does modern watchmaking.

Legacy Beyond the Dial

By the time of his death in 1799, John Arnold had reshaped the future of navigation. His chronometers guided ships across oceans with confidence previously unimaginable. They underwrote safer trade routes, faster naval deployments, and the expanding reach of maritime nations.

Yet Arnold’s name is often overshadowed, caught between the mythic brilliance of Harrison and the later industrialisation of timekeeping. Without Arnold, Harrison’s achievement might have remained a singular triumph rather than the foundation of a global system.

Arnold was the bridge between genius and utility, between invention and adoption. He understood that the true measure of innovation is not whether it works once, but whether it can be trusted everywhere.

A Place Among the Greatest

To call John Arnold one of the greatest horologists of his time is not to diminish Harrison, but to complete the story. Harrison discovered the path; Arnold paved it. His work ensured that the marine chronometer became not a curiosity of genius, but a dependable companion to every navigator who trusted their life, and longitude, to the ticking of a spring.

In the steady beat of a chronometer at sea, Arnold’s legacy still resonates: precision made practical, brilliance made useful, and time, at last, made navigable.

Following his father’s death in 1799, John Roger Arnold took on the business and continued the development and refinement of marine chronometers, ensuring that his father’s technical legacy endured into the next generation of precision timekeeping.

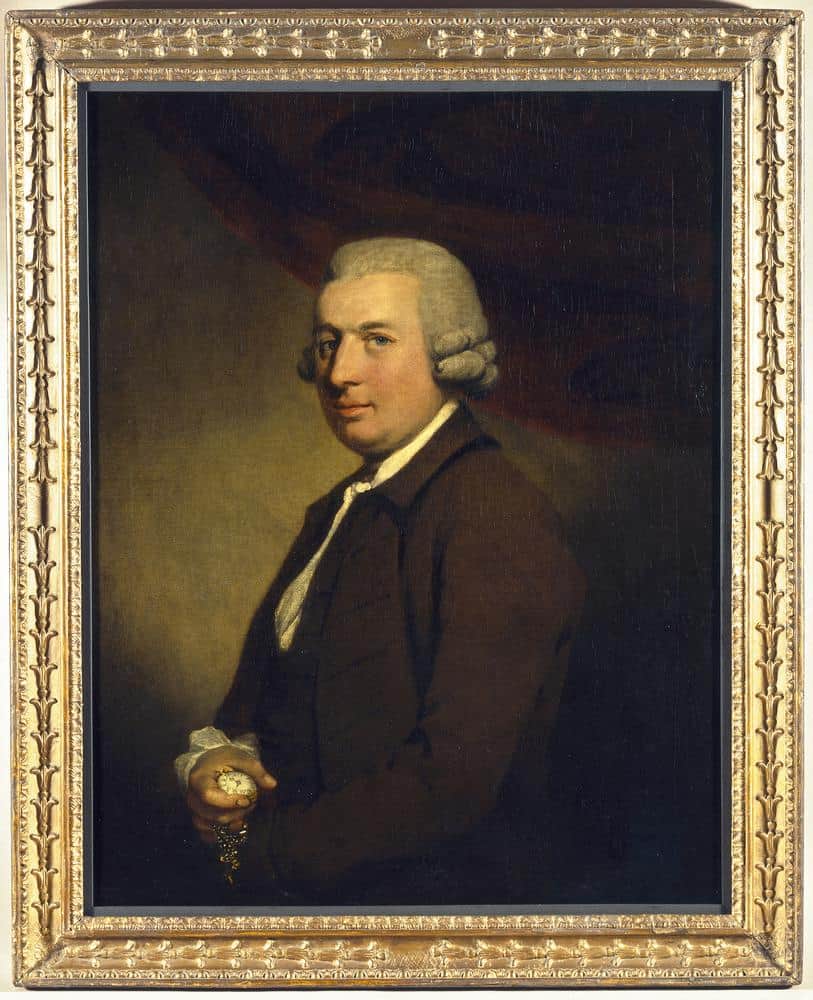

Hero Image: Oil painting; portrait of John Arnold in brown coat and vest; holding a watch. Attributed to: Chamberlin, 1760-1770. © The Trustees of the British Museum