Where Timekeeping Stopped Ticking and Started Conducting.

In the long lineage of timekeeping, the story is usually told in ticks: the swing of a pendulum, the recoil of an escapement, the heartbeat of a balance wheel.

But in the 19th century, something remarkable happened—time stopped being released by gears alone and began flowing through wires.

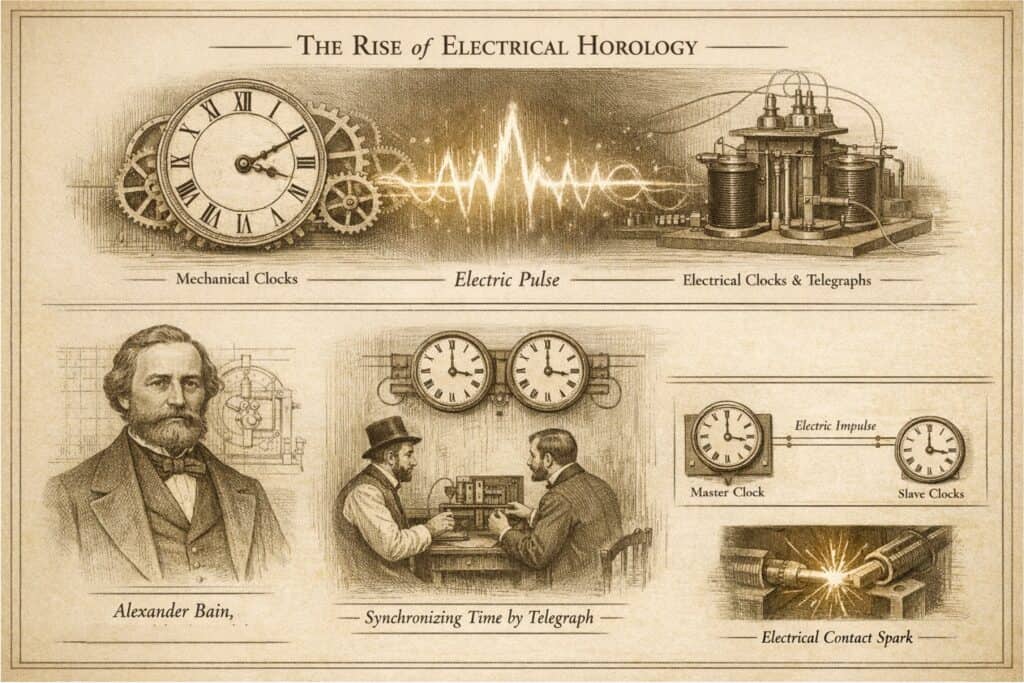

Electrical horology, the science and craft of measuring time using electricity, was not born from a desire to replace mechanical clocks, but to connect them. It emerged from a world rapidly being stitched together by telegraph cables, railway timetables, and scientific ambition. Accurate time was no longer a luxury of observatories and clock towers—it was becoming a networked necessity.

The First Spark

The earliest pioneers of electrical timekeeping were experimenters, not traditional clockmakers. In 1840, Scottish inventor Alexander Bain unveiled one of the first electric clocks, driven by electromagnetic impulses rather than a mechanical spring. His vision was bold but imperfect, a proof that electricity could move time, even if it couldn’t yet master it.

Almost simultaneously, Charles Wheatstone and William Fothergill Cooke were revolutionising communication with the telegraph. They soon realised a profound truth: if electricity could transmit messages, it could also transmit moments. And so began the first experiments in synchronising distant clocks through electrical signals—an idea that would transform both horology and the modern world.

The Age of Connection

By the 1850s, the concept evolved beyond single experimental clocks. Electric impulses were being used to:

- Synchronise public clocks across cities

- Standardise time along expanding railway networks

- Regulate observatory clocks with unprecedented precision

- Control “slave” clocks from a central “master” clock, laying the foundation for time distribution systems still used today

Timekeeping was shifting from local mechanics to shared infrastructure. The clock was becoming a node, not an island.

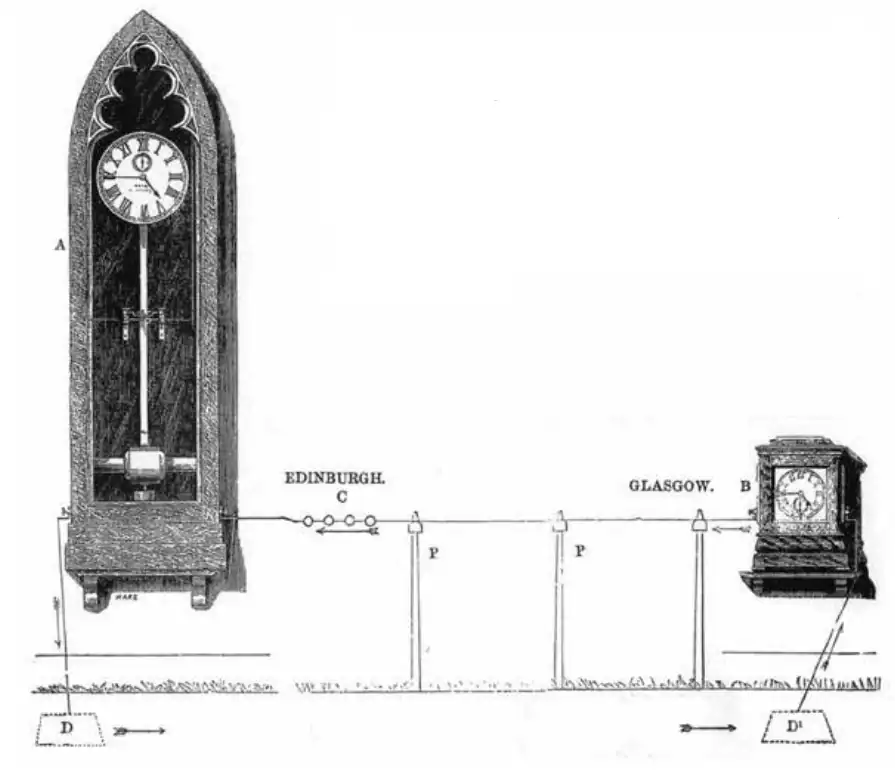

Telegraphs were a vital safety innovation on the railways, enabling the introduction of block working. Under this system, each train was assigned a clear section, or ‘block’, of track, managed by a signal box and controlled through line side signals. Telegraph communication allowed signallers to coordinate effectively, knowing precisely where trains were, what they were doing, and when it was safe to move them.

Timekeeping was equally crucial. A master clock at the Royal Observatory in Edinburgh controlled station clocks along the route, reflecting Alexander Bain’s implementation of a Universal Time system.

Clockmakers Meet Engineers

This new age forced an unlikely collaboration. Traditional horologists, masters of wheels and pinions, now found themselves working alongside electrical engineers, physicists, and telegraph technicians. The challenge was no longer only how to keep time—it was how to deliver it without distortion, delay, or interference.

Precision timekeeping was no longer a matter of craftsmanship alone, but of signal integrity, resistance, inductance, and power stability. The question became: How pure can a pulse be? How synchronised can the world become?

A Quiet Revolution

Unlike quartz clocks or atomic time, electrical horology never had a single dramatic moment of supremacy. Its revolution was quieter, practical, and deeply embedded in the invisible systems of everyday life. It didn’t just change how clocks worked—it changed how clocks worked together.

It was the moment humanity learned not just to measure time, but to share it.

Collecting Electric Clocks

Electric clocks continue to command high values at auction. This example above realised £40,800 when sold at Bonhams in 2011. The arched case with a full length front door set with a brass bezel over an arched glazed door to a moulded base edge, the signed and numbered 12 inch silvered Roman dial with blued steel hands, the movement of rectangular brass plates united by four turned pillars, the ‘scape wheel impulsed by a steel pallet on a hinged brass arm, the wood rod pendulum suspended from a bracket mounted on the velvet lined backboard and terminating in a large brass hollow cylindrical bob mounted on a curved brass arm, the backboard further set with a pair of insulated contacts. An almost identical example, number 175 is at the National Maritime Museum. The case to the current clock is partcularly fine, with excellent colour and figuring.

As always, the price depends the maker, quality, provenance and importance of the clock. Examples from the Eureka Clock Co. Ltd, Smiths and Gents are more reasonable in terms of cost.

Hero Image: Electric clock of the Bain type, 1840-1877. Science Museum Group © The Board of Trustees of the Science Museum.