In this occasional series, we will explore the life and achievements of the greatest and most respected horologists of their time. This feature will focus on Thomas Earnshaw, the engineers’ horologist, who made precision timing fit for purpose.

In the roster of great horologists, Thomas Earnshaw occupies a curious position. His name lacks the instant recognition of Breguet or Harrison, and yet the instruments shaped by his work quietly guided ships across oceans, underpinned naval supremacy, and defined marine chronometry for more than a century. Earnshaw was not a romantic innovator nor a courtly watchmaker, but he was, instead, the engineer’s horologist—the man who took precision timing out of the realm of fragile genius and made it robust, repeatable, and fit for service.

For collectors, Earnshaw’s importance lies not in decorative flourish but in architecture, restraint, and intent. His legacy is found in clean plates, spare mechanisms, and the ruthless elimination of anything that did not serve accuracy at sea.

A World Defined by Longitude

By the late 18th century, the problem of longitude was no longer theoretical. John Harrison had proven that timekeepers could determine longitude at sea, but his solutions—extraordinarily ingenious—were not scalable. The Royal Navy did not need singular marvels; it needed instruments that could be produced in numbers, repaired dockside, and trusted aboard warships and merchantmen alike.

This was the world Thomas Earnshaw entered: a Britain whose global ambitions depended on practical chronometry.

The expansion of British naval power demanded timekeepers that could survive months at sea and deliver consistent precision.

Early Life and Entry into Watchmaking

Born in 1749 in Ashton-under-Lyne, Lancashire, Earnshaw moved to London as a young man to complete his apprentice in watchmaking at a time when the city was the epicentre of precision horology. He trained during a period of intense experimentation, when escapements, balances, and temperature compensation were actively debated rather than standardised.

Unlike some of his contemporaries, Earnshaw showed little interest in ornamentation or novelty. His focus was functional clarity—how few components could reliably do the job, and how easily they could be made again.

Chronometry After Harrison

Harrison’s marine timekeepers had solved the longitude problem, but at a cost: complexity. They required exceptional craftsmanship, extensive hand-fitting, and careful oversight. For the Admiralty, this created a bottleneck. Precision existed—but it could not yet be industrialised.

The next generation of chronometer makers, including John Arnold and Thomas Earnshaw, addressed a different challenge: not can a chronometer be made accurate, but can it be made reliably and repeatedly.

Earnshaw’s answer would come in the form of a deceptively simple mechanism.

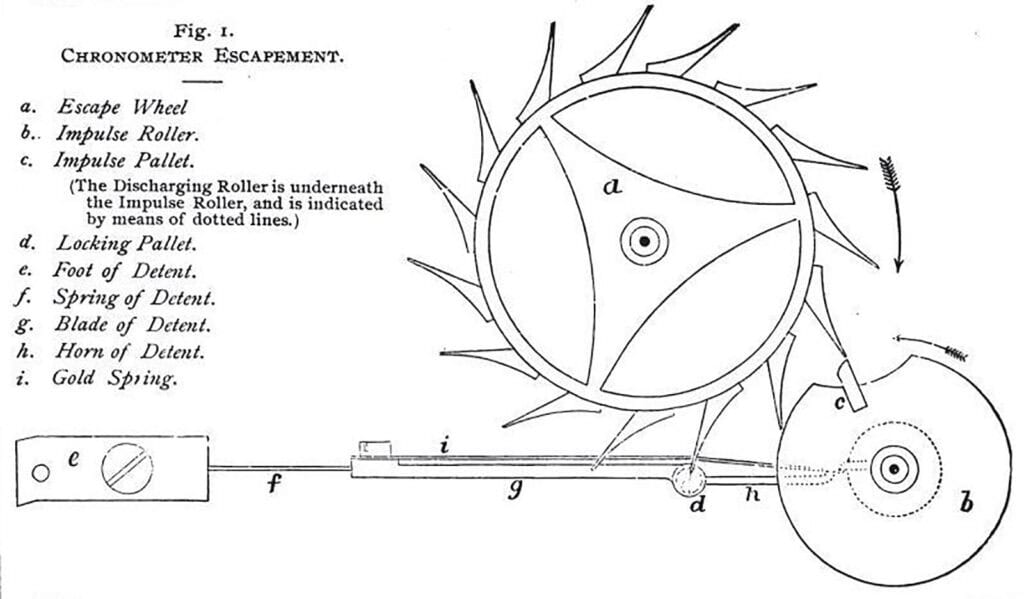

The Spring Detent Escapement

The spring detent escapement did not originate with Earnshaw alone. Pierre Le Roy had laid the theoretical groundwork, and John Arnold had produced workable early forms. Earnshaw’s contribution, however, was decisive: he simplified the escapement to its most practical expression (below).

By reducing the number of components and refining their interaction, Earnshaw produced a detent escapement that was:

- More robust

- Easier to manufacture

- Less prone to failure

- Better suited to naval service

This was not innovation for its own sake—it was engineering discipline.

Earnshaw’s simplified spring detent escapement eliminated unnecessary complexity while preserving chronometric performance.

Rivalry with John Arnold

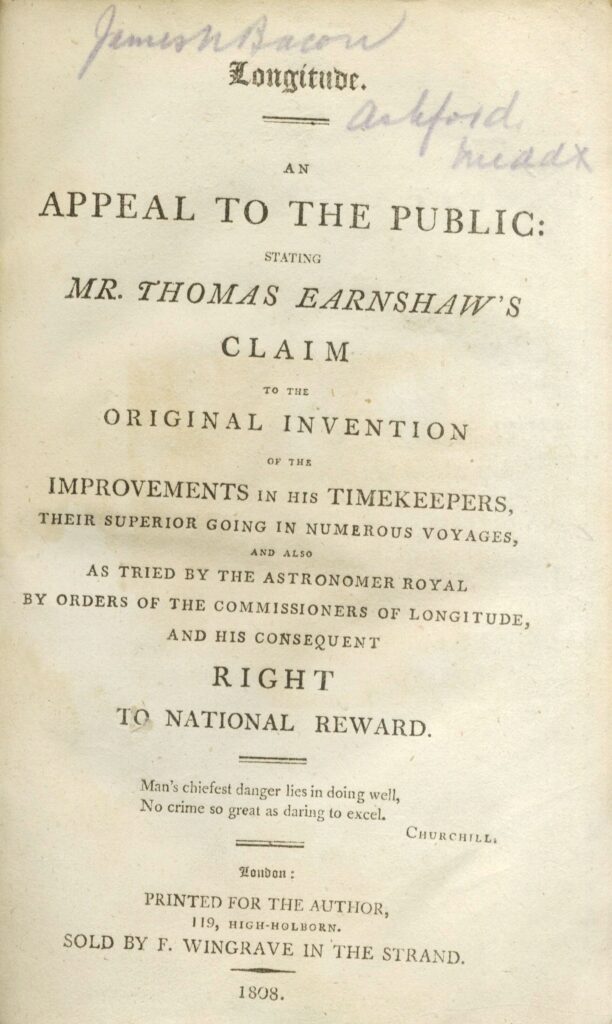

No discussion about Earnshaw is complete without addressing his rivalry with John Arnold. The two men worked in parallel, often arriving at similar solutions, and both contributed meaningfully to marine chronometry. Their conflict came to a head in 1805, when the Board of Longitude awarded £3,000 (approx. £325,000 in today’s money) jointly to Earnshaw and John Arnold’s son for improvements to the chronometer escapement. The arguments continued in a series of pamphlets and newspaper articles from supporters of each party (see below).

The decision was controversial. Arnold’s supporters argued precedence; Earnshaw’s advocates pointed to practicality and production. In truth, history suggests that Arnold advanced chronometry conceptually, while Earnshaw made it usable at scale.

Standardisation and Production

Earnshaw’s greatest achievement may not lie in a single invention, but in the standardisation of marine chronometer design. His principles influenced leading makers such as Barraud, Parkinson & Frodsham, and others supplying the Royal Navy.

Earnshaw-style chronometers shared:

- Consistent layout

- Predictable servicing requirements

- Repeatable performance characteristics

For the first time, chronometers became instruments the Navy could issue, maintain, and trust as a class.

Earnshaw Marine Chronometers

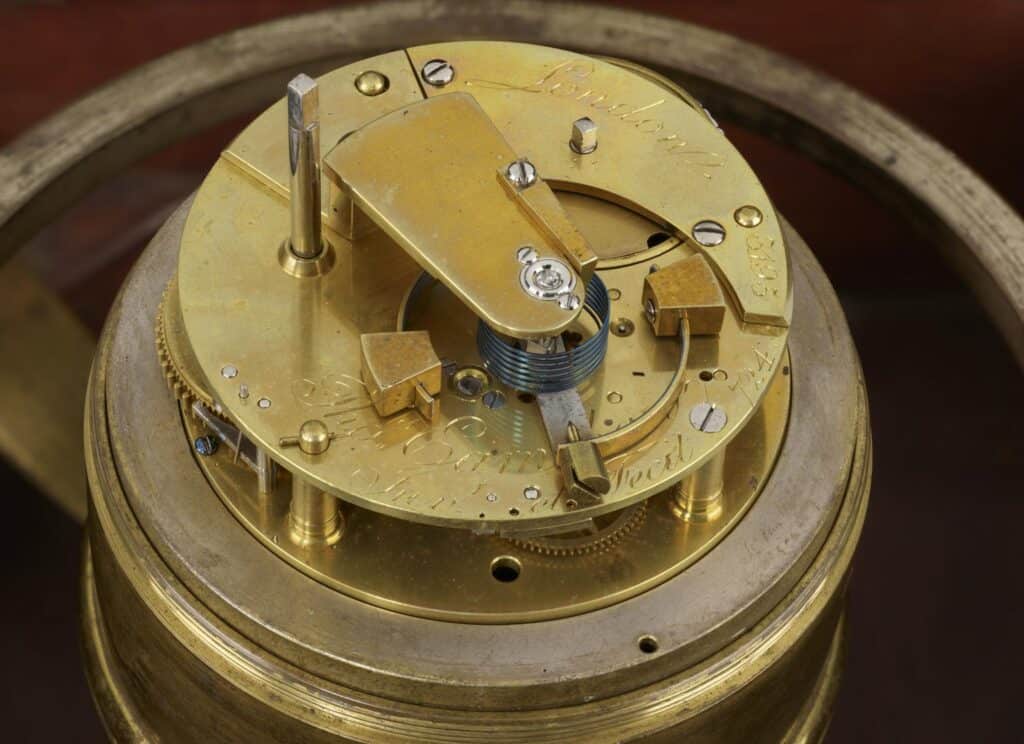

Following the work of Arnold, Earnshaw further simplified the designs of the pocket and marine chronometers into their modern, readily reproducible form.

Surviving Earnshaw chronometers reveal an aesthetic of discipline. Large balances, restrained finishing, and movements designed to be read and serviced rather than admired from afar.

Collectors who encounter original Earnshaw-signed pieces—or those built to his pattern—will notice:

- Functional engraving

- Logical component placement

- Minimal decorative excess

Naval Power and Global Reach

Earnshaw’s chronometers and deck watches were not luxury objects; they were strategic assets. Their widespread use enabled safer navigation, tighter fleet coordination, and more reliable global trade routes. Precision timekeeping became, quite literally, an instrument of empire.

This silver pair cased deck-watch by Thomas Earnshaw was used for navigation by Capt. George Vancouver (c.1755 – 1798) on board HMS Discovery, during his famous voyage surveying the West Coast of America (1791 – 5). The movement with spring detent escapement and two-arm bi-metallic compensation balance has wedge weights. It is signed on the movement ‘Thos. Earnshaw London Invt. et Fecit. no 1514’.

While no single chronometer won a battle, the quiet accuracy of Earnshaw’s designs underpinned Britain’s maritime dominance in the 19th century.

Later Years and Obscurity

Despite his immense contribution, Earnshaw did not enjoy lasting fame or financial security. He died in 1829 with little public recognition, overshadowed by figures whose work was either more visible or more easily romanticised.

For decades, his name lingered mainly in technical footnotes—respected by professionals, overlooked by popular history.

Why Collectors Should Care

Modern horological scholarship has been kinder to Earnshaw. Today, he is recognised as the man who ensured that chronometry was not merely possible, but practical. Without Earnshaw, marine chronometers might have remained experimental instruments rather than standardised tools.

For collectors today, the Earnshaw detent represents one of the purest expressions of chronometric design. Its visual austerity—long, clean lines and unobstructed geometry—reveals a philosophy rarely seen in later, more decorative movements. These escapements are not beautiful because they are ornate; they are beautiful because nothing is wasted.

In an age that often celebrates complication and display, Earnshaw stands as a counterpoint—a master of restraint whose legacy lies in reliability, clarity, and purpose. For those who collect not just watches, but ideas, Thomas Earnshaw remains one of the most important horologists of his time.

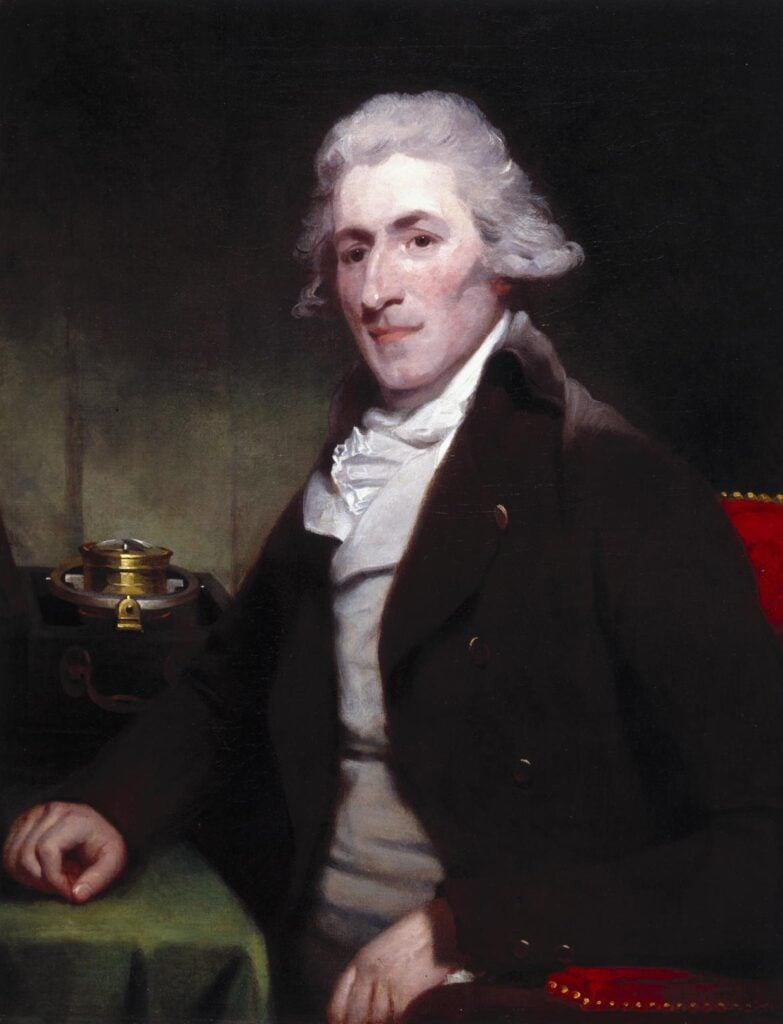

Hero Image: Portrait of Thomas Earnshaw, attributed to Sir Martin Archer Shee, 1798. Science Museum Group Collection © The Board of Trustees of the Science Museum