Time may be intangible, but the craft of measuring it has always been profoundly physical. For centuries, horologists—clockmakers and watchmakers—have relied on tools that translate abstract cycles into ticking reality. From soot-darkened forges to laser-lit clean rooms, the evolution of horological tools mirrors humanity’s broader journey from brute force to microscopic precision.

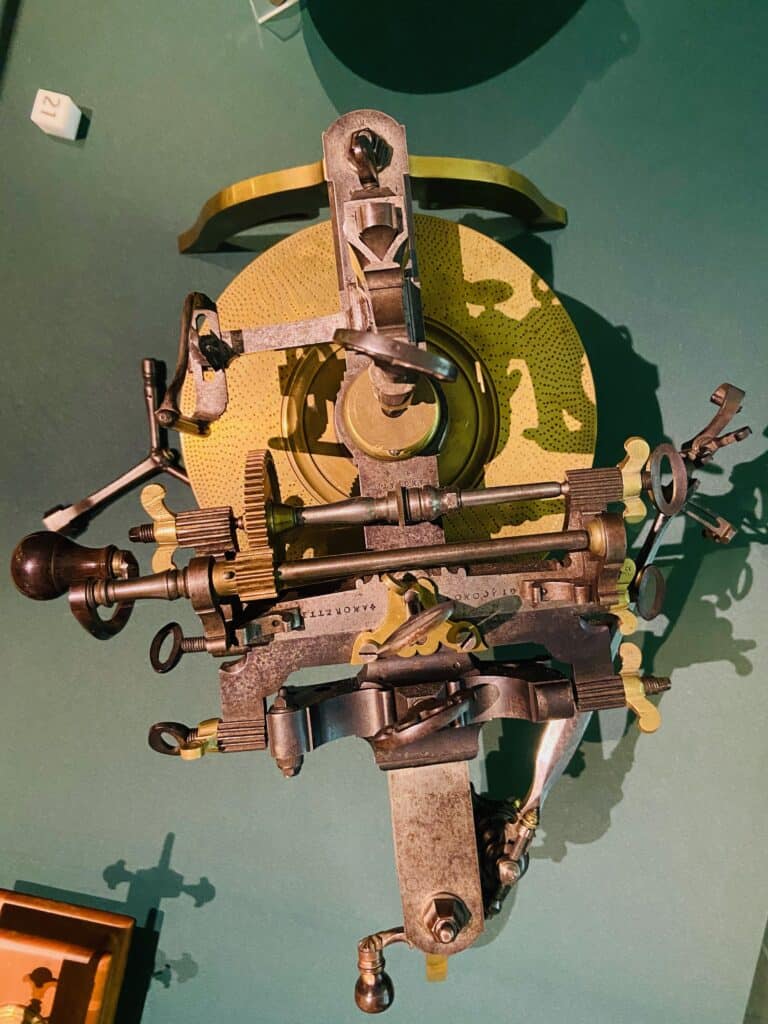

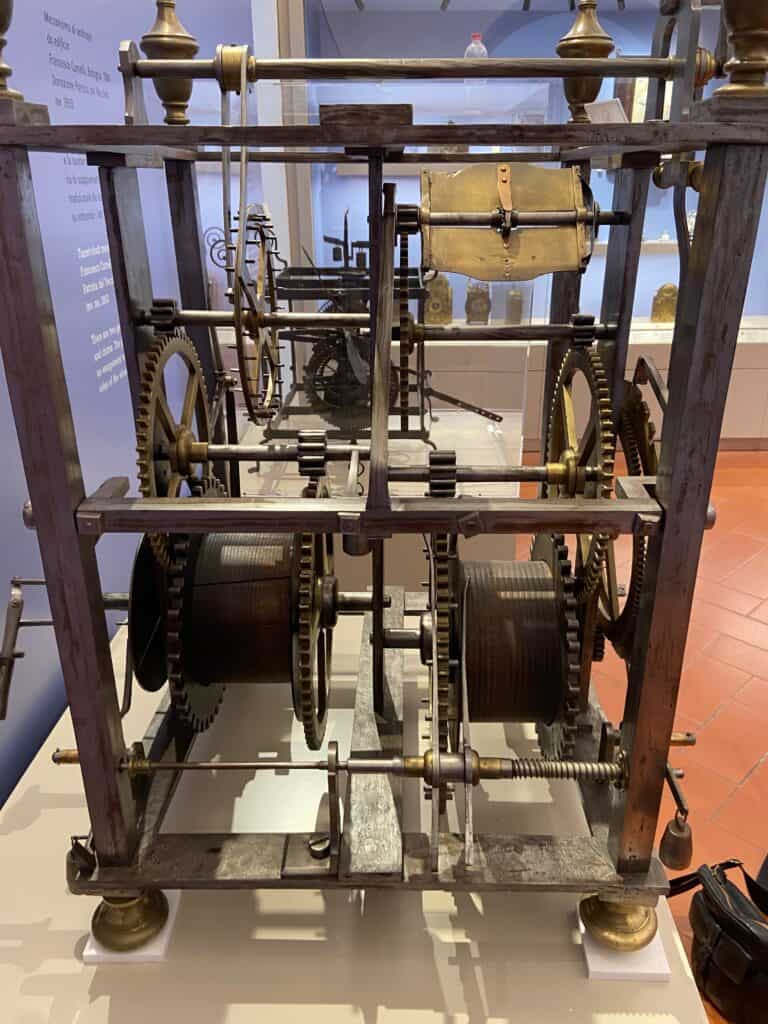

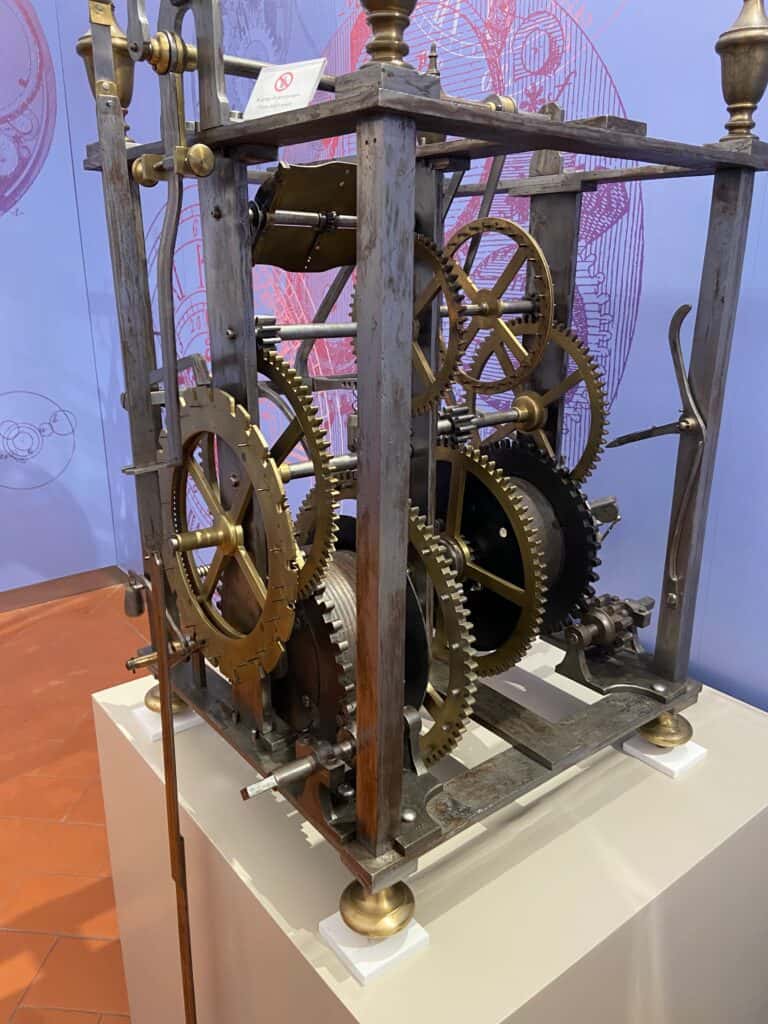

To trace the history of horological tools is to follow the evolution of craftsmanship itself, from blacksmiths’ forges to sterile clean rooms humming with lasers. My interest in these tools was piqued when I visited the Galileo Museum in Florence to see the Italian Hours Exhibition (August 2023) which included wonderful examples of horological tools that were exquisitely made. They were often as beautiful as the timepieces they went on to make.

Forged Time: The Medieval Origins

The earliest mechanical clocks of medieval Europe, appearing in the late 13th and early 14th centuries, were monumental machines. Installed in church towers and civic buildings, they were built not by specialist “watchmakers” but by blacksmiths and locksmiths. Accordingly, their tools were heavy and agricultural in spirit: hammers, tongs, chisels, files, anvils, and bellows.

Tools were heavy and elemental: hammers, anvils, tongs, chisels, punches, and above all, files. Gear wheels were forged and filed by hand, their teeth shaped by eye rather than measurement. Precision was coarse, but durability mattered more than accuracy. These clocks did not track seconds; they governed social order—prayers, markets, and labour.

The file, born of this era, would become one of the most enduring horological tools, still indispensable centuries later.

During our ‘Object Handing’ sessions at the Clockmakers’ Museum, we show visitors an 18th century ‘screw plate’ (below), that was most likely made by an apprentice and used to make screws for clock and watchmakers in their workshop. Every workshop would have their own version of this type of tool, which meant that each ‘hand-made’ screw would be in essence a unique creation – at this time standardisation was some way off.

Horological tools were essential items in the workshop, but often they were made as decorative items as we can see from the ivory handle for a tool signed ‘Tho. Tompion Fecit’ below. The authenticity of this tool has been variously believed and disbelieved over many years. The present view is that it probably is Tompion’s work and may have been intended to hold a watchmakers’ brooch.

Shrinking Time: Renaissance Ingenuity

As timekeepers shrank from towers to tables and pockets during the Renaissance, tools followed suit. Spring-driven clocks and early watches demanded finer work and greater consistency.

The bow drill emerged as a vital tool, allowing small, precise holes to be drilled in brass plates. Foot-powered lathes—often handmade by the watchmakers themselves—enabled the turning of pivots, arbors, and wheels. Dividers and calipers became common, introducing comparative measurement into the workshop.

This was the age when horology began to separate from general metalworking. Tools became specialised, and the workbench evolved into a carefully organised system rather than a general workspace.

Measuring the Invisible: The Enlightenment

The 17th and 18th centuries transformed timekeeping accuracy—and tools had to keep up. The pendulum, balance spring, and jeweled bearings demanded surfaces finished to extraordinary smoothness.

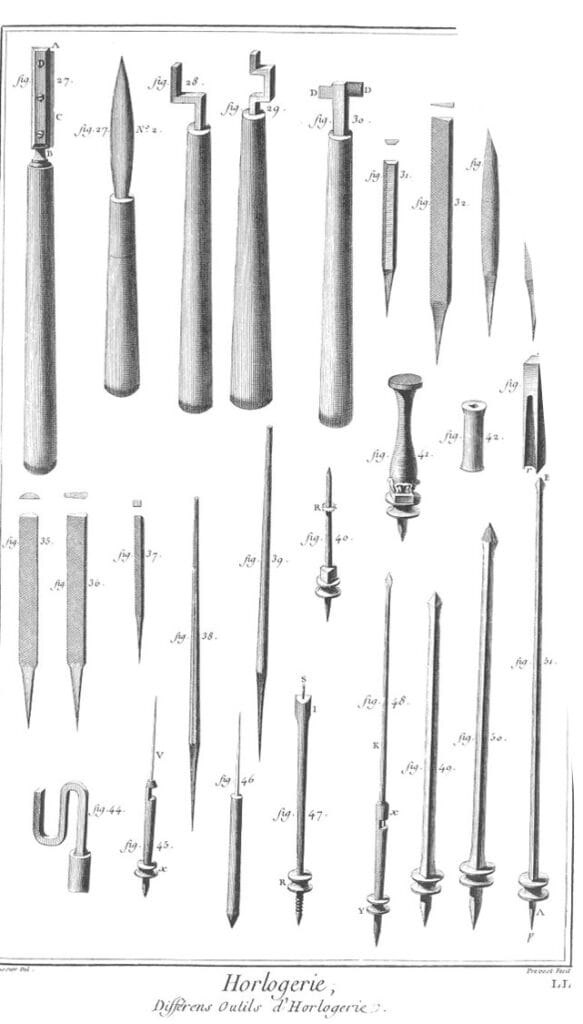

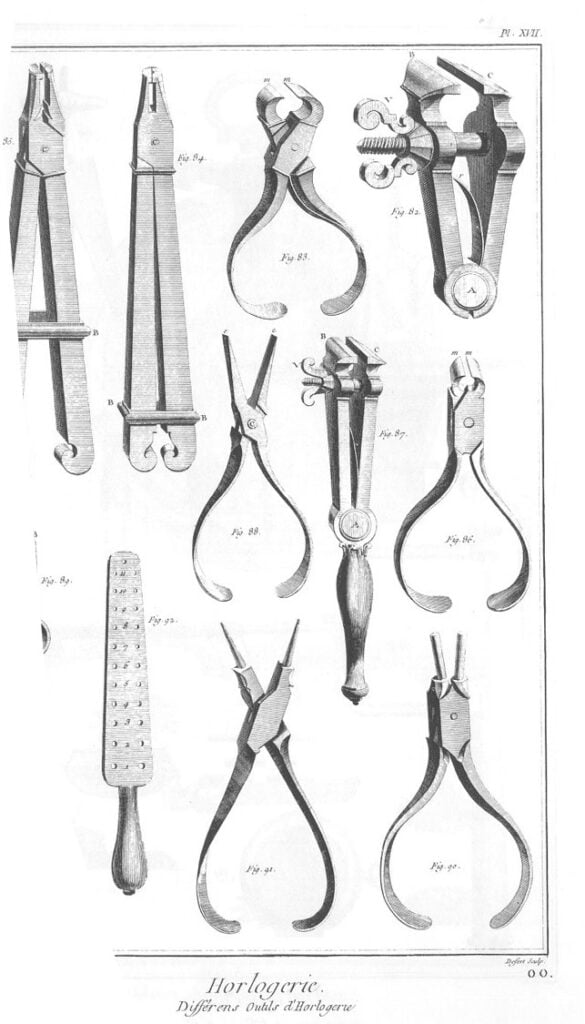

Watchmakers refined their lathes with interchangeable chucks and tool rests. Burnishers polished pivots to mirror finishes; gravers cut steel with surgical control. Jewel-setting tools allowed rubies and sapphires to be seated with minimal stress, reducing friction and wear.

Measurement became king. Depthing tools ensured correct gear meshing, gauges checked thicknesses, and increasingly precise calipers reduced reliance on intuition alone. Still, every measurement ended in the hand and eye of the craftsperson.

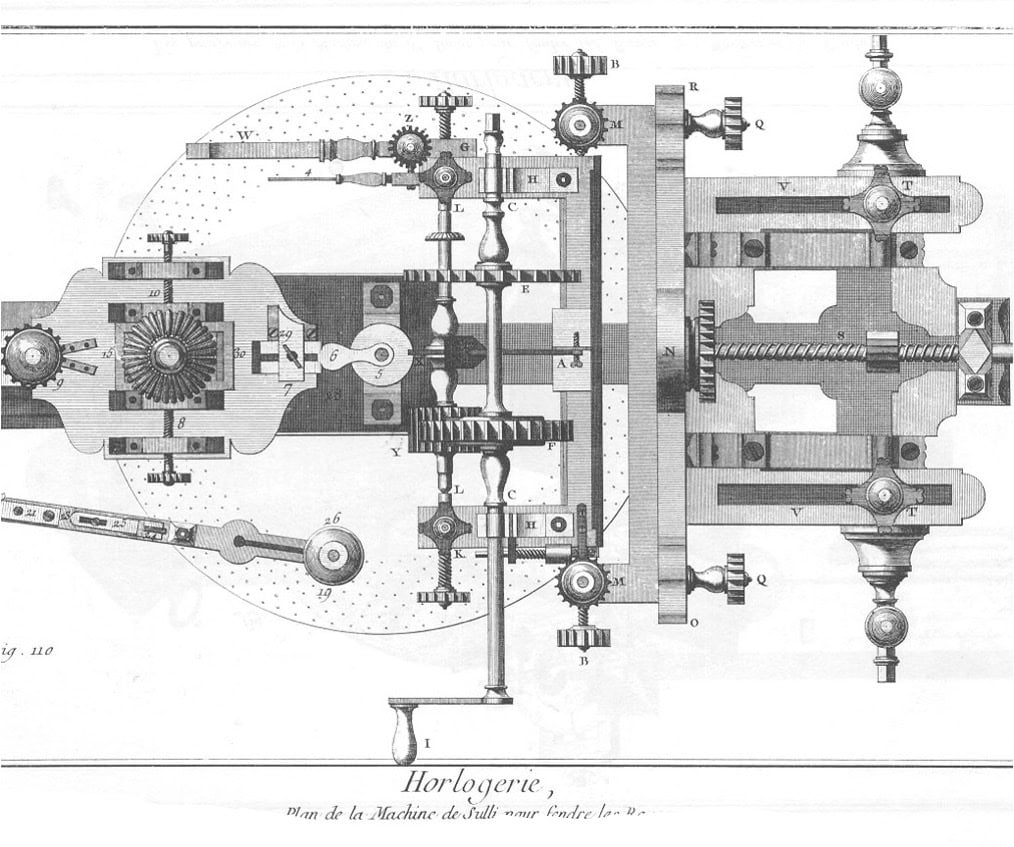

This is a small screw-cutting lathe which was designed for cutting fusees. A fusee is a tapering drum of hyperbolic section with a screw-like groove cut on it, on which is wound a cord connecting the main spring of a clock or watch with the driven mechanism. ltwas formerly used for maintai ning a copstant driving torque as the spring unwinds.

Machines and Multiplicity: The Industrial Revolution

The 19th century introduced a philosophical shift as radical as any technical one: interchangeable parts. To achieve this, horology embraced machines.

Gear-cutting engines, screw-making machines, milling tools, and jigs filled factories, particularly in the United States. These tools enforced uniformity, allowing watches to be assembled—and repaired—using standardized components.

Yet hand tools did not disappear. Screwdrivers became smaller and more refined. Tweezers, loupes, and files remained central, especially in finishing and adjustment. The watchmaker’s bench became a hybrid space, where machines created parts and hands perfected them.

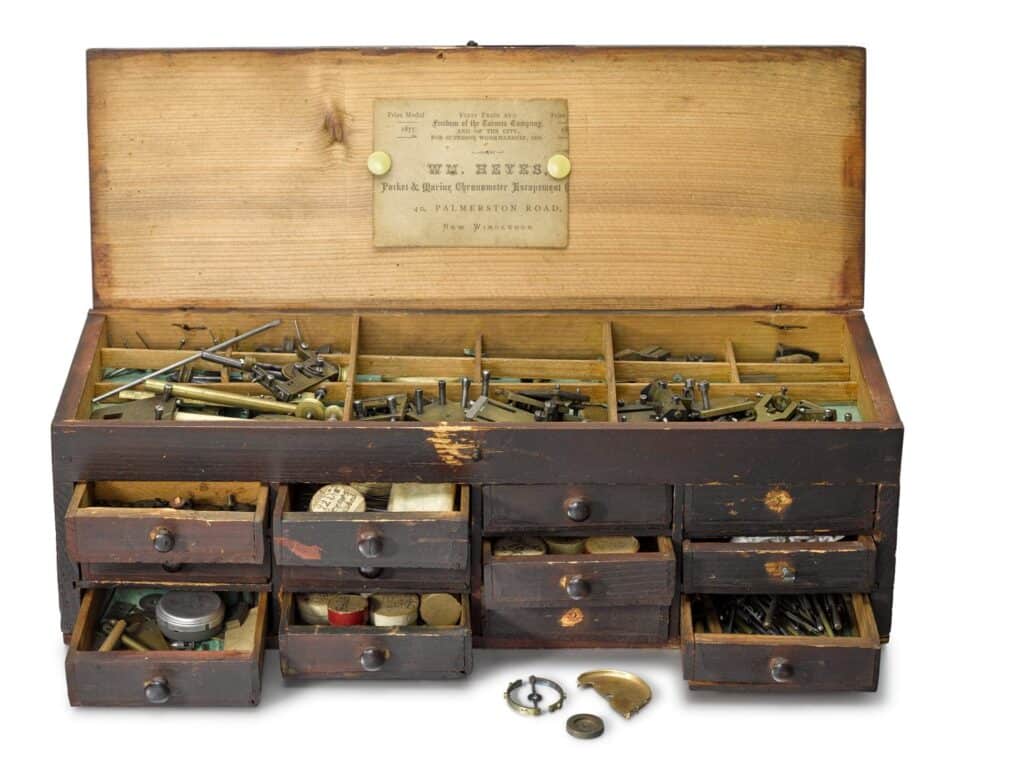

This miniature chest of tools was used by the very fine London escapement maker and finisher William Heyes. It contains an astonishing array of vital equipment, including tools for polishing roller edges, screw arbors for turning wheel blanks, shoulder tools, swing tools, stakes, clamps, rounding tools, brooches, tongs, underhand polishing tools, scrapers and oilers.

Electricity and Electronics: The 20th Century

Electric motors transformed the workshop. Lathes no longer relied on foot power. Polishing motors replaced hand laps, and ultrasonic cleaners revolutionised maintenance by removing dirt invisible to the naked eye.

New diagnostic tools appeared: timing machines that ‘listened’ to escapements, balance poising tools of extreme sensitivity, and mainspring winders that improved safety and consistency.

The quartz era added oscilloscopes, frequency counters, and circuit testers to benches once dominated by brass and steel. Horological tools now spanned both mechanical and electronic worlds.

Microns and Memory: The Modern Workshop

Today, high horology operates at the edge of the visible. CNC machines cut components to tolerances measured in microns. Lasers weld balance springs. Silicon parts are etched using semiconductor techniques in dust-free clean rooms.

And yet, the paradox of modern horology is how much remains unchanged. The same files, gravers, tweezers, and loupes sit beside machines worth millions. Many master watchmakers still prefer vintage tools, claiming they offer better tactile feedback—better conversation between hand and metal.

Tools as Witnesses of Time

Horological tools are not merely instruments; they are historical documents. Worn handles, polished edges, and softened knurling speak of thousands of hours at the bench. They bear the marks of concentration, repetition, and mastery.

In a craft devoted to measuring time, these tools quietly accumulate it. They remind us that no matter how advanced the technology, horology remains a human art—one where steel, patience, and judgment shape the relentless flow of seconds.

From fire-blackened anvils to laser-guided welders, the tools of the trade tell a story not just of innovation, but of continuity: proof that even as timekeeping advances, the soul of the craft still rests firmly in the hands that hold the tools.

Hero Image: Machine for cutting teeth on medium-diameter gear wheels, made by Giacomo Amoretti, c.1769. Part of the Italian Hours Exhibition at the Galileo Museum in Florence (July 14 – October 15, 2023).