Time Through the Ages is a four part series commissioned by Worn & Wound, a place to discover watches and experience enthusiasm. In this first instalment, we provide an overview of the major players and accomplishments from the early days of English watch and clock making.

Many people believe that the origin of modern-day watchmaking came from the Swiss, but it all started in England back in the early 17th century. The 1620s saw a desire by clock and watch makers to establish a dedicated company as a representative body, but this was met with opposition from the other livery companies – guilds or associations in the City of London to regulate and protect the interest of their members – in particular the Blacksmiths.

The Worshipful Company of Clockmakers eventually received its Royal Charter on 22nd August 1631. The Charter created a corporate body for all the Clock and Watch makers in the City of London and within a radius of ten miles around, with regulatory powers covering England and Wales. It specified that the new Fellowship should be governed by a Master, three Wardens and ten or more Assistants who would form a Court. The first Master was David Ramsay, former Chief Clockmaker to King James I.

The notable figures who played significant roles in the early history and establishment of the Worshipful Company of Clockmakers included, Nicholas Cratzer, a German astronomer and mathematician who served as the clockmaker to King Henry VIII of England. He is believed to have made significant contributions to the art of clockmaking in England during the 16th century.

Nicholas Oursian, a French clockmaker who was granted the first Royal Charter by King Charles I. Charles Gretton, a prominent London clockmaker who served as the Master of the Company in 1671 and 1672. Daniel Quare, an English clockmaker known for his invention of the repeating watch mechanism in 1680.

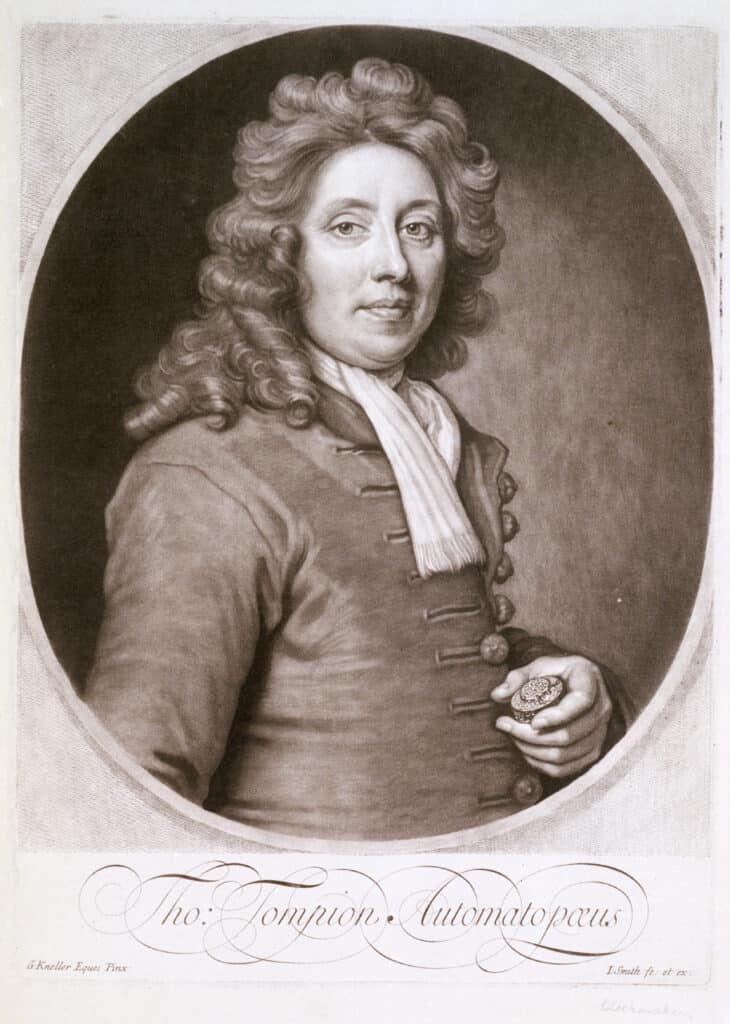

Thomas Tompion, often regarded as the ‘Father of English Clockmaking’, Tompion was one of the most celebrated clockmakers of the late 17th and early 18th centuries. He was a key figure in the early years of the Worshipful Company of Clockmakers, becoming Master in 1703, and worked for the physicist Robert Hooke, who explored the concept of using a spring to regulate the oscillations of a balance wheel. Tompion was so revered, that on his death, he was buried at Westminster Abbey.

© The Clockmakers’ Charity

Businesses were thriving in the City of London with watch and clock makers prospering, as wealthy merchants wanted to show their wealth with the finest watches available. However, there were two events that impacted greatly on business, with the Great [bubonic] Plague of London in 1665-66 followed by the Great Fire of London in September 1666, which was a ‘blessing in disguise’ as it cleared any lingering plague.

Courtesy of Clocktime Digital Museum

The epi-centre of English watch making was based around Clerkenwell in the City of London (the site of today’s Hatton Garden jewellery trade). At this time, there was an influx of Huguenot craftsmen migrating from France, following the revocation of the Edict of Nantes (1685) by Louis XIV which deprived the French Protestants of all religious and civil liberties. Many Huguenot’s became watch and clock makers and joined the Clockmakers’ Company, among the most famous being Justin Vulliamy (below), who immigrated to England in the early 18th century and became renowned for his precision clocks and watches.

Watches and clocks were the preserve of the wealthy upper echelons of society. The Golden Age of English Clockmaking spanned the late 17th century to the early 19th century. This period was marked by significant advancements in both technology and craftsmanship, leading to the creation of some of the world’s most exquisite and innovative timepieces. During this time, England was at the forefront of horological innovation, with clockmakers such as Thomas Tompion, George Graham, John Harrison, and Thomas Mudge making ground-breaking contributions to the field.

George Graham, a contemporary of Tompion, further advanced the field with his inventions, including the cylinder escapement and the deadbeat escapement. His work laid the foundation for modern clockmaking and greatly influenced subsequent generations of horologists. The early years of the 18th century was a time of great exploration. When ships left Greenwich harbour and set their timekeepers when the Time Ball dropped at 1pm, they were then at sea for weeks and months at a time.

They were able to navigate by the stars to find their latitude (north to south), but they couldn’t establish their longitude (east to west) position. The inability to accurately determine longitude posed a significant challenge to navigation, leading to numerous shipwrecks and loss of life. This led to the Government in 1714, forming the Board of Longitude, to award a prize for finding longitude at sea. The prize was set at £20,000 (today worth £5million).

Royal Museums Greenwich

John Harrison – a trained carpenter – developed the marine chronometer revolutionising navigation by enabling sailors to accurately determine their longitude at sea. He created five timepieces, H1 to H5 over a 40-year period. In 1770, the wonderful H5 chronometer was personally tested by King George III at his observatory in Richmond and this timekeeper helped secure Harrison the last part of his Longitude prizemoney.

The Clockmakers’ Museum/Clarissa Bruce

© The Clockmakers’ Charity

Thomas Mudge, known for inventing the lever escapement, made significant contributions to the development of precision timekeeping. His innovations played a crucial role in the evolution of watches and clocks, ensuring greater accuracy and reliability. The one drawback to Harrison and Mudge’s watches and clocks was they were too expensive. This brought in the likes of Thomas Earnshaw and John Arnold to produce marine chronometers and watches. Earnshaw’s development of the detent escapement and Arnold’s marine chronometers were particularly significant contributions to navigation and timekeeping.

The Clockmakers’ Museum/Clarissa Bruce. © The Clockmakers’ Charity

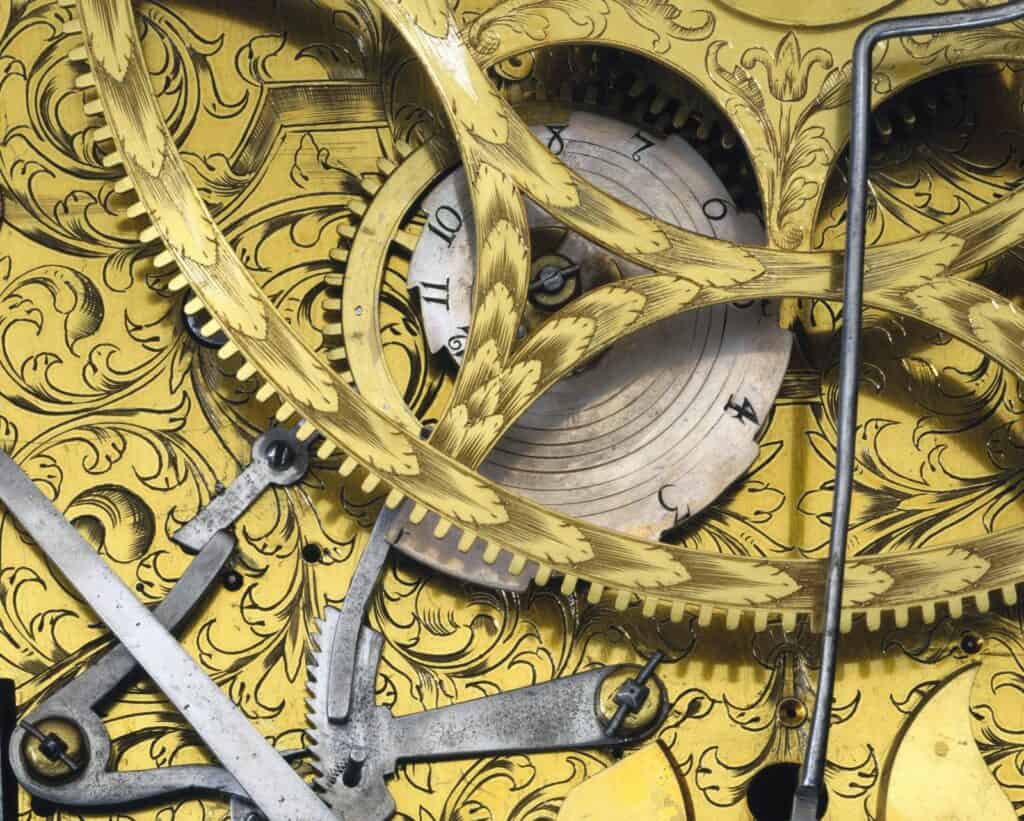

The Golden Age of English Clockmaking was also characterised by a flourishing of craftsmanship and artistic expression. Clock and watch makers adorned their creations with intricate designs, elaborate engravings, decorative elements, showcasing their mastery of both mechanics and aesthetics, such as polychrome enamelling (see below).

c1750. The Clockmakers’ Museum/Clarissa Bruce. © The Clockmakers’ Charity

These English clocks and watches were highly sought after by royalty, nobility, and wealthy patrons across Europe, to the Ottoman Empire, Chinese Emperors and beyond. Their reputation for quality, precision, and elegance solidified England’s position as a leading centre of horological excellence during this golden era. The middle of the 19th century saw the beginning of the decline of English watch and clock making. The Industrial Revolution had a profound impact on the industry in England. Mass production techniques and the mechanisation of manufacturing processes led to increased efficiency and accessibility of timepieces. It was at this time when competitive markets were growing, including the United States of America, Switzerland, France, and Germany. It was the mechanisation of production at the Waltham Watch Manufacture that enabled them to produce hundreds (eventually thousands) of watches every day. It was during the Cent Centennial Exposition of 1876 in Philadelphia, that Waltham exhibiting their manufacturing process to the world. The Swiss watch federation sent two Observers (Spies!) to see what they were up to and report back – but that is a fascinating story for another day!

English watches were still being created and finished by hand which meant that they were comparatively expensive and took time to finish. It was only the surge in exploration that kept English watchmaking companies in business with the Admiralty ordering thousands of marine timekeepers for ships, which took between 5 to 10 chronometers on each journey. They also needed repairing and restoring after each trip.

The move from pocket watch to wristwatch came to the fore during WW1, with soldiers needing to know the time in the trenches. From this time onwards, the watch making industry developed and grew exponentially. While the advent of quartz technology in the 20th century and changes in consumer preferences have transformed the watchmaking industry, the legacy of the Golden Age of English Clockmaking endures. The masterpieces created during this period remain prized possessions and are celebrated for their historical significance and enduring beauty.

The next feature in the series is titled Abraham-Louis Breguet’s Genius of Invention and is available on Worn & Wound.