This new series focuses on the Greatest Horologists You’ve Never Heard Of showcases the incredible clock and watchmakers that made some of the finest pieces primarily during the Golden Age of English Clock and Watchmaking.

David Ramsay was a renowned Scottish watchmaker and clockmaker who was born in the late 16th century. During the 17th century he was recognised as a prominent figure in the world of horology and appointed as the first Master of the Worshipful Company of Clockmakers and watchmaker to two Kings prior to the English Civil War.

Born in Scotland, Made in London

David Ramsay was born around 1580 near St. Andrews, in the county of Fife, Scotland and grew up as part of a relatively well-off family in a proudly Scottish household. He later moved to London, England, where he gained recognition for his skills in clockmaking. Ramsay was a mechanical genius and produced some of the world’s most extraordinary horological masterpieces – clocks and watches that are arguably works of art. Although he rose to the top of his field as a watchmaker, operating from the seat of power in London, he struggled chronically with money, eventually falling out of royal favour and winding up in a debtors’ prison.

In 1594, he was apprenticed to the master armourer Henry Smith who was appointed Royal Armourer to King James VI of Scotland. Ramsay’s training in metalworking certainly played a crucial part in his later development as a watch and clockmaker. This required specialist knowledge and training, such as hardening and tempering steel, and smelting iron ore to obtain a more uniform steel of higher quality.

He would have also been trained in quality control, finishing and engraving. These skills would serve him well in the production of the most difficult part of all in any clock or watch: the main steel driving springs.

Normally, an apprenticeship was completed after seven years, and then the apprentice was allowed to take up a free citizenship to practise their trade. Ramsay did not follow the usual apprenticeship path and there is no record of him working in Scotland. We know he travelled to Paris in 1610. Although details are vague, it is known that Ramsay met with the French King’s clockmaker, Denis Martinot to purchase clocks and bring them home to Scotland. It is believed that he spent three-years in Paris, and it is reasonable to surmise that he received some sort of training as a watchmaker whilst there.

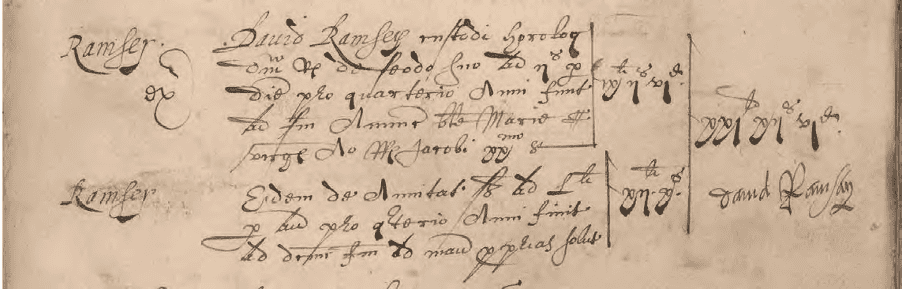

Although Ramsay is usually thought of as a watchmaker, he also made clocks. One survives from this period, pre-dating Ramsay’s arrival in London. This is the ornately engraved gilt table clock, now housed at the Victoria and Albert Museum (V&A) in South Kensington, London.

The movement of this spring-driven, striking table clock has been extensively altered, probably in the late 17th century. Its baseplate is signed by David Ramsay, but some of the later alterations to the clock were done by the French clockmaker Louis David with the brass plate bearing his name covers Ramsay’s signature. The case is likely to have been imported from France, since French clocks of this period have the same square base and domed bell-cover pierced with openwork.

On the base is an engraved scene showing James I, with his two sons Henry and Charles, holding the Pope’s nose to a grindstone. On the right a Cardinal and three friars view the proceedings with dismay. The scene is taken from a German engraving and was inspired by the settlement made in 1609 between Spain and the Estates General of the Netherlands. The settlement was regarded as a great blow to papal power since it was an alliance between a Roman Catholic and a Protestant state. The clock must have been made shortly afterwards, when the issue was still topical.

A Master by Royal Appointment

In 1613, Queen Elizabeth I died, and King James VI of Scotland became King James I of England. King James I was a significant figure in British history, born on the 19th of June 1566, he became King of Scotland in 1567, following the abdication of his mother, Mary, Queen of Scots. He ascended to the English throne, uniting the crowns of England and Scotland.

The King summoned Ramsay back from France and offered him two coveted positions in the royal household: Groom to the Privy Chamber and Page to the Bedchamber. Ramsay was also tasked with the responsibility of caring for the King’s clocks and watches, effectively becoming the Royal Clockmaker. His joint royal remuneration was £250 per annum – in today’s money £52,000 – not bad for a 28-year-old watchmaker from Fife!

As Keeper of all His Majesty’s Clocks and Watches, and subsequently Clockmaker Extraordinary in 1613, Ramsay was an extremely influential member of the Royal Household. He used this to his benefit, but despite trading in London, he often signed his movements ‘David Ramsay Scotus’, probably to show his Royal allegiance.

As a member of the King’s Privy Council, he found himself at the very heart of power in London and had the private ear of the King; he was in a far more influential position than of the person merely tending to the King’s clocks and watches.

By the 1620s London was a thriving and important centre for the craft of watch and clockmaking and Ramsay continued as Royal Clockmaker under King Charles I. Ramsay was named in the Clockmakers Charter, granted by Charles I, and was appointed as the first Master of the Worshipful Company of Clockmakers.

The Worshipful Company of Clockmakers is one of the historic Livery Companies of the City of London, founded in 1631. This organisation was established to oversee the craft and trade of clock and watchmaking, ensuring quality standards, regulating apprenticeships, and protecting the interests of its members. The company has played a significant role in the development and advancement of horology in England and still does today.

Ramsay’s Greatest Horological Masterpieces

David Ramsay was commissioned around 1618 to make an exceptional astrological watch – a mechanical marvel and work of art unto itself. It was so complex that it rivals many modern complication watches with its appearance and number of indications. Typically for its time, it was made to be worn as an ornament, on a chain around the waist or neck.

It was extremely expensive, and the inclusion of King James I’s royal portrait and motto indicates that it was most likely commissioned by the King himself, who was also Ramsay’s royal patron.

On its dial face, the watch gives seven indications for

- Time of day

- Annual calendar

- Sign of the zodiac

- Day of the week

- Lunar phase

- Lunar date

- Ruling planet

Each of the underlying mechanisms was engineered using complex mathematics to get the multiple gears to work together. Occupying the top and bottom halves of the dial face are two large dials: the annual calendar disc on top, and the time dial on the bottom.

The silver top and bottom are engraved with scenes from Ovid, but their inside faces have King James I’s coat of arms and a portrait of the King himself. The silver case band with red detailing has Chronos with his scythe and St James under his sun hat between floral branches.

The movement shows the hour, the day – sign, name and deity, the month – name and date together with the sign of the Zodiac, the age and phase of the moon, and the planet hour – useful in astrology. The movement is made of gilt and spaced by elegant pierced Egyptian pillars. The watch is signed ‘David Ramsay Scotte Me Fecit’.

I had the honour to be in the presence of this extraordinary watch, and close-up it’s even more wonderful than it looks in photographs. The craftmanship is astonishing particularly given that it is over 400 years old. It sold at auction for more than £1 million (including fees) in December 2015, which was four-times its pre-sale high estimate of £250k.

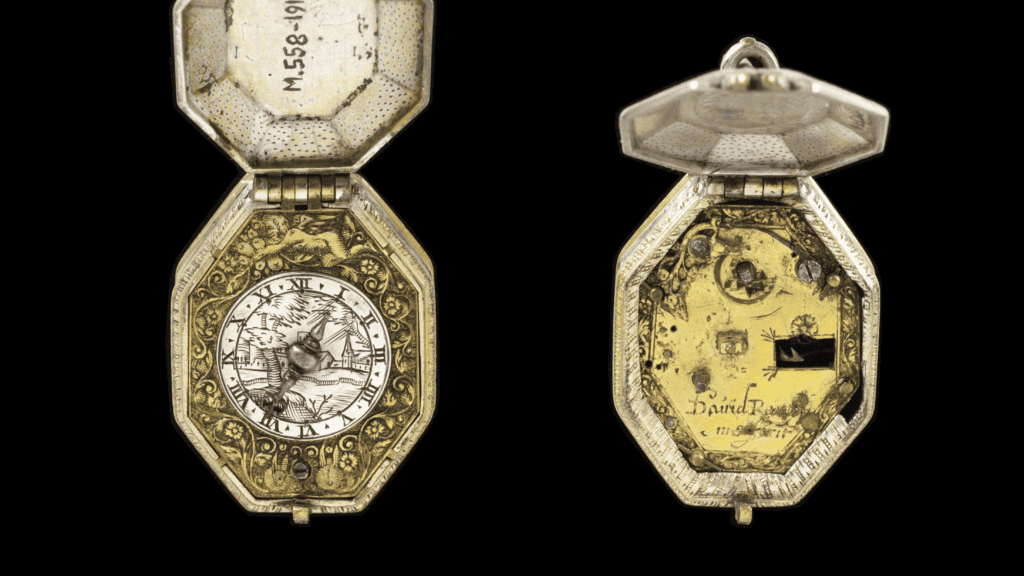

Given his privileged position, Ramsay received commissions from the ‘great and the good’ of society. This beautifully decorated small silver and gilt brass watch was perhaps made for a Lady at the Court of King James I. It is engraved with the Annunciation and the Nativity, with the movement is signed ‘David Ramsay me fecit’, probably made in London. At this time watches were for the very wealthy and it would have been worn on a chain around the neck as a status symbol.

A key aspect of running a 17th century watch and clockmaking business was to travel to the continent to meet with trusted suppliers, discuss requirements, and see the latest fashions, and reinforce the personal connections that would allow Ramsay to be sure he could supply top quality items to his wealthy and exacting clients.

“Mr Ramsay of the Bedchamber has arrived here. He was heretofore a verie probable favourite and a gentleman of trueth of a verie fayre temper…whoe will take this tyme of the Kinges progresse to see the nearer countries abroad.”

Letter from The Hague, dated 13th of July 1615, between Sir Henry

Wotton and William Trumbull

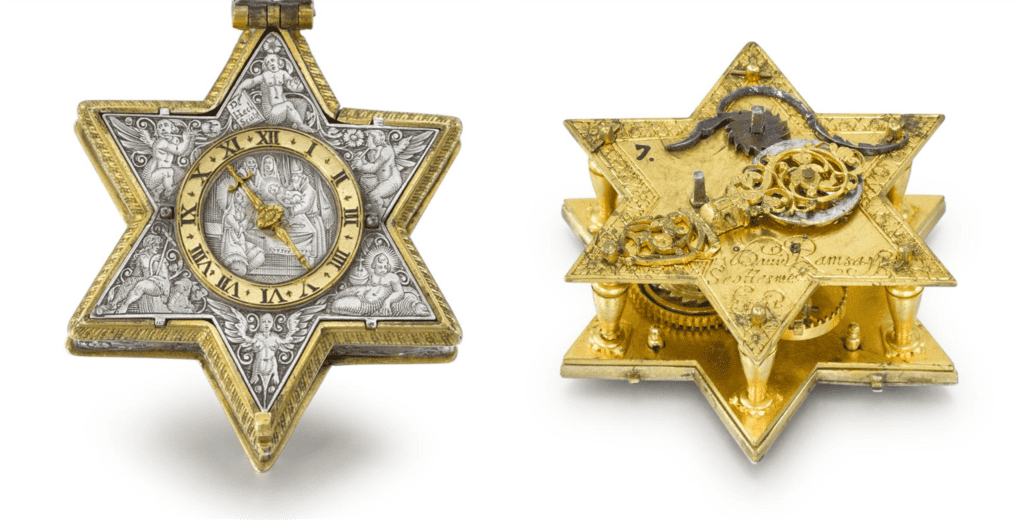

This silver watch in the shape of a six-pointed star was made by David Ramsay in c.1625. The silver case is engraved with scenes of the nativity on all surfaces. The silver dial has an engraved centre, while the six points of the star have representations of angels of which that above XII holds a shield bearing the legend ‘de Heck Sculp’ (sculpted by de Heck). The fusee movement has a verge escapement, pinned-on balance cock and ratchet wheel set-up. It is signed ‘David Ramsay, Scotus me fecit’.

This watch was concealed for many years behind a tapestry at Gawdy Hall, Norfolk and only discovered in around 1790. As a result, it is in remarkable condition. The words ‘de Heck Sculp’ on the dial refer to Gérard de Heck of Blois, France, active from 1608 – 1629. Blois was a centre of craftsmanship for creating intricately designed timepieces in the 17th century.

Did the six-pointed star shape have any religious significance? As intriguing as this may be, we will never know why it was made in the shape of the modern-day ‘Star of David’!

Ramsay was an exceptional movement maker and designer, but the production of his timepieces was dependent on several expert craftsmen for engraving and enamelling. We have seen that two of his finest timepieces showed the skills of master engraver Gérard de Heck. He was a historically significant watchmaker and was part of a broader European tradition of skilled craftsmen who contributed to the development of horology during a period of significant advancement in timekeeping technology.

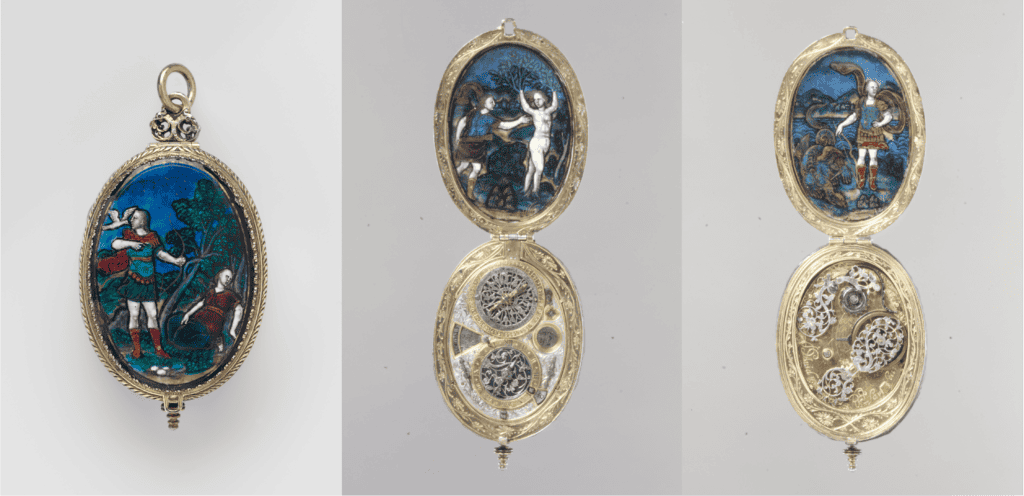

This exquisite watch by Ramsay was made in c.1620 and is profusely decorated with beautiful polychrome painted enamels. The enamel plaques are initialled I.R. which is probably for Jean Reymond who was active between 1615-1632. Reymond was a notable French watchmaker and is recognised for his contributions to the craft of horology, particularly in the region of Limoges, which was also known for its artistic and a centre for decorative enamel work.

Reymond’s watches often featured elaborate and detailed enamel designs, making them both functional timepieces and works of art. These watches were highly valued not only for their timekeeping capabilities but also as luxury items and symbols of status.

An Inauspicious End

While Ramsay had been a favourite of King James I, after his death in 1625, he never enjoyed the same level of confidence with King Charles I. When Charles became King, he inherited his father’s Privy Council, including Ramsay. However, with the execution of King Charles I on the 30th of January 1649, the London clock trade was hit by a deep recession. Ramsay’s workshop slowly ran out of work, and his patrons and customers went elsewhere.

Without Charles’ protection, Ramsay was jailed in the Gatehouse Prison for debtors. He spent four years in prison. After the defeat of the King, Oliver Cromwell, the leader of the new Commonwealth, asked Ramsay to disclose whom the King had given gifts and to help him track down any of the King’s possessions. Cromwell asked for Ramsay’s help so that he could repossess these ‘gifts’ and raise money for the new state. In exchange, he offered a commission to pay off his debts and be released from jail, which meant that he abandoned his loyalty to his previous royal employer by taking up Cromwell’s offer. By 1653, Ramsay was living in Holborn, London, and in 1659, he died as a pauper, leaving behind his wife Sarah and their son William.

Ramsay had a fascinating and often precarious life right at the centre of power, serving two consecutive kings and living through a Civil War led by the Commonwealth’s Lord Protector, Oliver Cromwell. Despite these tumultuous times, he managed to produce some of the finest, most complex watches the world has ever seen.

David Ramsay’s overall contribution to the craft of watchmaking and clockmaking is remembered as an important chapter in the history of horology, marking him as one of the key figures in the early development of precise timekeeping instruments.

Fittingly, Ramsay signed most of his work ‘Scotus me fecit’ which translates to ‘Scotland made me’.

The next in the next series The Greatest Horologists You’ve Never Heard Of is now available on Worn & Wound.

Hero image: King James I of England and VI of Scotland by Daniel Mytens, 1621. Image courtesy of the National Portrait Gallery