A series of features to look at what drives a collector to collect? How do they go about seeking out items they want for their collection? In this new series, we look back through time to highlight the greatest collectors of all time and showcase their particular area and passion for collecting.

David Arthur Wetherfield (1845-1928) was a prominent collector of English domestic clocks, amassing one of the most significant private collections of its kind. His collection, known as the Wetherfield Collection, particularly from the ‘Golden Age’ of English clockmaking (late 17th to early 18th century), consisted of over 220 clocks, including longcase clocks, bracket clocks, and lantern clocks. The collection was particularly notable for its focus on English craftsmanship, featuring works by master clockmakers such as Edward East, Daniel Quare, Joseph Knibb, George Graham and Thomas Tompion (known as the ‘Father of English Clockmaking’).

David Wetherfield lived in Blackheath, Southeast London, and for many years, was the senior partner of the coal exporters and marine insurance brokers W.S. Partridge and Co. The firm went out of business when he retired at an advanced age. His interest in clocks was said to have started when he wanted to own a longcase (grandfather) clock, employing an ‘expert’ to advise him on which one he should buy. Apparently, he was deceived into buying a worthless imitation and when he realised this, decided to put together a collection of timepieces that would be unsurpassed by anyone else.

His entire collection was housed at his home in Blackheath and remained there until his death, aged 83 in 1928. According to one visitor, the house was three or four storeys high with a basement, where grandfather clocks stood on every other stair of a wide staircase. It was said that in the large basement, grandfather clocks stood shoulder-to-shoulder against the wall with others standing back-to-back down the centre of the room. On the ground floor bracket clocks were arranged side-by-side on shelves, with several of his ’special clocks’ from the great makers such as Tompion and Knibb etc were in the lounge on the first floor.

It must have been extraordinary to experience such an incredible collection of some of the greatest horological items all in one place. Unfortunately given the age, there are no photographs of Wetherfield’s collection in situ, however, one can imagine the amazing array of clocks ticking away and chiming on the hour!

Before callers left the ‘House of Clocks’ they had to promise Mr. Wetherfield that they would not disclose his address, because he had an abhorrence of opportunist dealers, plaguing fakers and persistent American millionaires. Some of the wealthiest people in the world had sought to raid his collection, but none had succeeded.

“Such an array of choice examples as Mr. Wetherfield has gathered, affords an opportunity of obtaining information never before presented, and the large number of excellent photographic reproductions here given enables one to compare the styles in vogue as well as the conceits of different makers throughout the whole period. Again and again, I have gone over this collection with delight and profit, and I think no one who has a regard for the work of our old craftsmen could inspect these clocks without being amply repaid for his trouble.”

F.J. Britten from his introduction in the book, ‘Old English Clocks (The Wetherfield Collection)’ published in London by Lawrence and Jellicoe Ltd in 1907

This small weight-driven 30-hour lantern or ‘house’ clock (above) with alarm work by Peter Closon was similar to one included in the collection. The clock originally had a verge and balance-wheel escapement but was converted at some point to anchor and long pendulum. It would have had a twelve-hour duration. The dial is engraved with tulips with a steel hand and is signed ‘Peter Closon Neere Holburn Londini fecit’. c.1655.

Peter Closon was a prolific maker of such clocks and ran a large workshop at Holborn Bridge. He was an original subscriber to the Clockmakers’ Company, and became an Assistant and a Warden, but probably died (c.1660) before he could serve as Master.

This Joseph Knibb London walnut veneered hooded wall clock is very similar to one in the collection. It has walnut frets, seated on a carved walnut buttress, with Huygens endless cord weight driving both the single hour hand movement and the hour strike. The dial plate is finely engraved with flowers in each corner as spandrels and in the centre, further flowers erupt from a vase.

The 1670s was a pivotal period for astronomy and navigation. In March 1675, King Charles II appointed John Flamsteed as his astronomical observator, becoming the First Astronomer Royal and in August of that year the king laid the foundation stone for the Royal Observatory at the top of the hill overlooking Greenwich Park and the Queen’s House. These two acts in 1675 led ultimately to the longitude of The Royal Observatory becoming chosen as the Prime Meridian of the whole world!

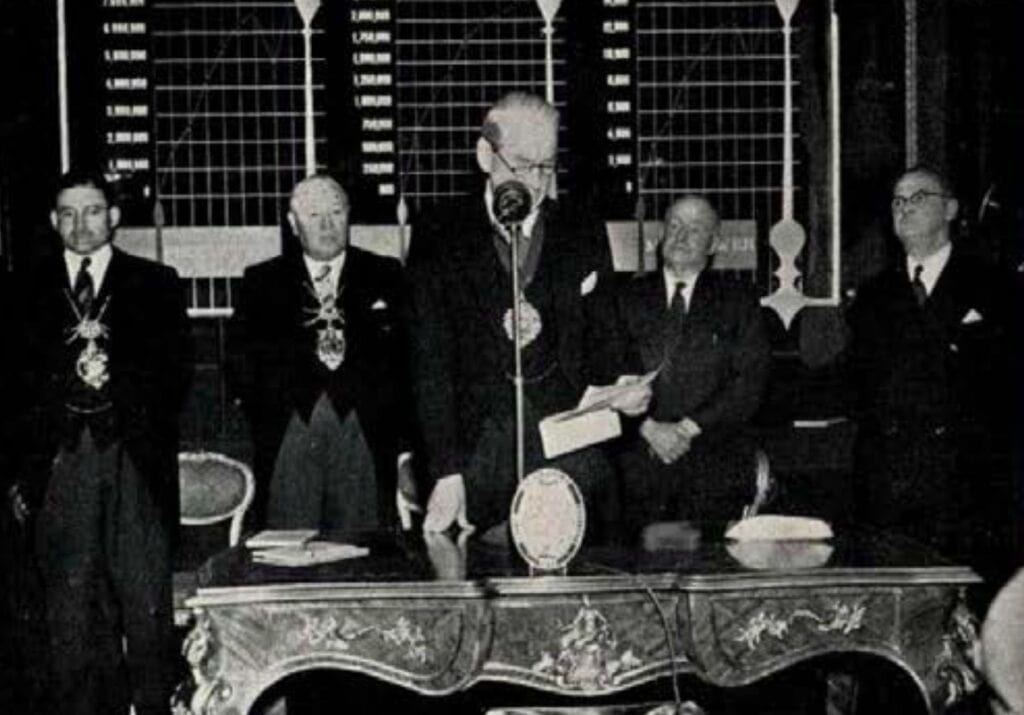

Five Centuries of British Timekeeping Exhibition

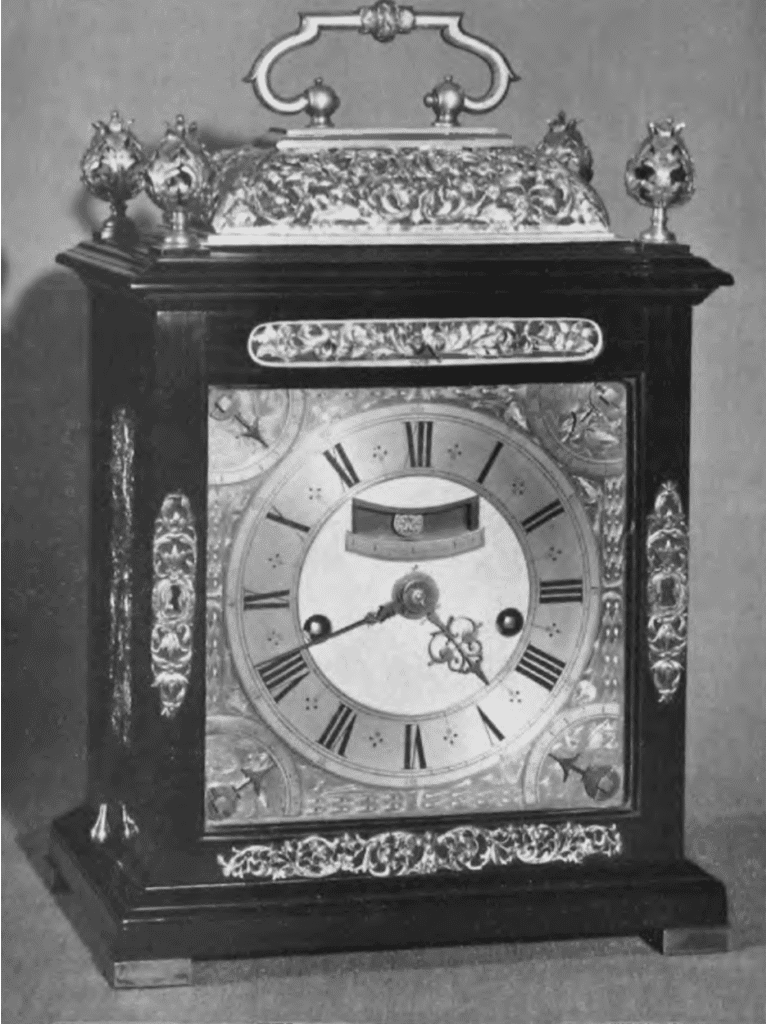

This is the magnificent so-called ‘Record Tompion’ made for King William III and probably resided in Hampton Court Palace was one of the standout items at the ‘Five Centuries of British Timekeeping’ a major exhibition that took place at the Goldsmith’s Hall in the City of London between the 3rd and 8th of October 1955.

At the time the exhibition was described as “The Greatest Publicity Ever Given to British Clocks and Watches” by the Horological Journal, the industries trade publication. It was opened by the Lord Mayor of London, Sir Seymour Howard (below) who said it was “A remarkable portrayal of great traditions of the re-born industry.”

This was the first and probably the only time the ‘Record Tompion’ clock was on show to the public in the United Kingdom. There were many items from the Wetherfield collection at this major exhibition in London.

The name of the clock has stuck since the collection was placed in the hands of the London auctioneer W.E. Hurcomb by the executors of Wetherfield’s will prior to sale. The term appears to be for publicity purposes and relates to the ‘record breaking’ sum it was deemed to be worth. It is a three-month striking longcase clock in a burr walnut case with silver and gilded mounts. The clock stands at an imposing 10ft 2in (3.1m) and has a dial with a perpetual calendar showing month, number of days in the month, date, and corrects for leap years. Beneath the hood are four open-worked metal corner brackets, and on top are four silvered urn finials and a central figure of Minerva with her shield, with the cypher of William III below.

This important ebony eight-day striking and chiming bracket clock with gilt basket top by Tompion (below) was sold as part of the overall collection. It is known as the ‘Tulip Tompion’ due to the tulip patterned finials at each corner of the clock. It has a very complicated movement that will strike and if required repeat the hours and quarters at each quarter (known as grand sonnerie). The dial has a mock pendulum with the signature engraved below ‘Thomas Tomipon Londini Fecit’. There is only one other ‘Tulip Tompion’ case known.

Although his collection numbered 23 clocks by the master maker, Thomas Tompion also known as the ‘Father of English Clockmaking’, I believe the ‘Record Tompion’ clock was its ‘jewel in the crown’. It caused much debate and discussion at the time of the auction as to where it should have ended up. We will come back to the clock’s journey and value later as we now focus on the proposed auction following Wetherfield’s death.

Auction of the Wetherfield Collection

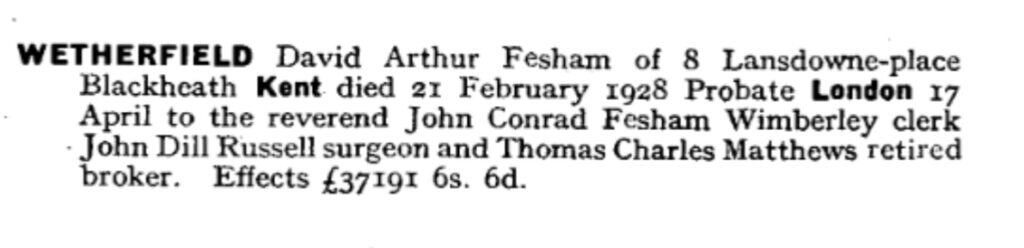

According to the probate records of the UK Government, the last will and testament of David Arthur Fesham (should read Fasham!) Wetherfield of 8 Lansdowne Place, Blackheath had a value for his ‘Effects’ of £37,191 6s. 6d. worth £1,976,260* in today’s money (see below).

As with most collectors, as detailed in his will, his interests seemed to have gone beyond just his clocks as he also states that “all my plate, linen, China, glass, books, pictures, prints, wines, liquors, furniture” be distributed equally between various members of his family.

Let’s now return to the auctioneer, W.E. Hurcomb, who tells a fascinating story of how he met Wetherfiled on the recently opened ‘Tupenny Tube’ – today known as the London Underground. He explains that he’d attended a rival’s auction sale which included a bracket clock by the ‘famous old Master’, Thomas Tompion. Hurcomb purchased the clock and took it home on the ‘tube’ (not sure anyone would do this today!). He was approached by an ‘immaculately dressed gentleman’ who surprised him by saying “Surely that is a Tompion.” It goes on to say that he was amazed by this as 90% of clockmakers would not know who ‘Tompion’ was, let alone a private gentleman. After a brief discussion, the gentleman introduced himself saying “My name is Wetherfield”, which resulted in a deal and payment by a cheque from Coutts and Co. (bankers to the Royal family) was exchanged before they reached the next station.

This appears to be the start a relationship that lasted until Wetherfield’s death and enabled Hurcomb to handle the sale by auction of the entire collection. It was the wish of Wetherfield that the collection be sold as a whole to one collector. In his last will and testament, Wetherfield stated that “his collection of old English clocks should be sold by public auction within twelve months of his death unless the appointed trustees are able to dispose of the collection privately at a fair market value within a reasonable time”. Prior to this he had expressly stated that his collection should not be acquired for America. The sale was held over the 2nd and 3rdMay 1928, with the whole collection being offered first in its entirety for a set price.

On the 1st of May 1928, a syndicate bought the collection paying £30,000 for the 222 clocks. It included Francis Mallet of the Bond Street antique dealer, Mallet and Son, well-known dealer-collector, Percy Webster and American furniture and clock dealer, Arthur S. Vernay of No.19 East 54th Street, New York. In today’s money this equates to £1,594,144*. This also meant that Wetherfield’s clock collection made up over 80% of his total estate on his death according to his will executed in April 1928.

After the Wetherfield sale, the William III Tompion was sold by Mallet’s for £3,000 (equivalent to £159,400* today) to an American collection and exhibited for several years at the Pennsylvania Museum. At the time it was reported that Mallet gave the British Government the opportunity to purchase the clock stating that the Victoria and Albert Museum has no specimen like it. This was to no avail as the clock went to the United States of America. It did return to the UK in 1934 having been bought by J.S. Sykes, a merchant involved in trade with the Near and Middle East for £4,000 (equivalent to £242,149* today). After the exhibition mentioned earlier ended, Sykes sold the clock privately back to the USA for £11,000, (although this resulted in a profit at the time, the equivalent value was £233,114* in today’s money resulting in a slight loss), to the Colonial Williamsburg living museum.

It was fascinating to read that the collection would have realised £1,970,000 in 1979, (equivalent to £9,489,499* today). This estimation was made by Donald de Carle who visited the collection several times. De Carle oversaw the clock and watch department for Garrard and Co., jewellers to the Royal family so was well placed to offer this valuation.

He was a Fellow and Medallist of the British Horological Institute (BHI) and a Liveryman of the Worshipful Company of Clockmakers. Throughout his career, de Carle authored numerous authoritative books that have educated generations of horologists and enthusiasts. He died, aged 96 in 1989 but his legacy endures through his publications, which continue to serve as essential resources for watch and clock repairers worldwide.

This is an early pendulum clock, by eminent London maker, Edward East. This would have been exactly the type of clock that Wetherfield sought for his collection, in fact he had several clocks by East amongst the collection. The relatively plain wooden case of this clock owes much to the design of the first Dutch pendulum clocks (first seen in Amsterdam in 1657) and marks it as an early product of the new technology of clockmaking in England. It is spring driven, with a duration of a single day, which was relatively unusual as most clocks went for eight days and strikes the hours on a single bell.

Inspiration for Modern Collectors

Wetherfield’s collection of antique clocks has had a profound and lasting influence on modern-day collectors and horology enthusiasts. His meticulous approach to curation, focus on craftsmanship, and dedication to historical preservation set standards that continue to shape collecting practices and the appreciation of antique clocks.

The collection covered all aspects of early English domestic clocks and highlighted the achievements of the ‘Golden Age of English clockmaking’. His focus on the master makers such as Thomas Tompion, George Graham, Joseph Knibb, Edward East and others brought attention to their artistry and mechanical ingenuity.

Modern collectors are inspired to seek out pieces from this era, and these makers are now considered the pinnacle of horological craftsmanship and continue to command premium prices in auctions. He set the standards for quality and his eye for excellence ensured that his collection included only the finest examples of clockmaking, emphasising exceptional mechanical precision, artistic merit in case design, engraving, decoration and the historically significance of the pieces.

He realised the value of provenance and was meticulous in documenting the provenance of his clocks, often including historical details about the makers, the era, and unique features of each piece. As most collectors know, this is a crucial factor in the valuation and desirability of antique clocks.

Wetherfield’s collection inspired the study of horology and the formation of groups such as the Antiquarian Horological Society (above) and the Watch Collectors Club (below). It led to a broader appreciation of the art and science and ensured others pursued horology as a field of study and practice. Prior to collectors like Wetherfield, French and Continental European clocks were often more celebrated for their artistic flair. His focus on English clocks helped solidify their reputation for precision, innovation, and elegance.

His dedication to preserving the best examples of English clockmaking ensures that these masterpieces remain appreciated and valued, inspiring both private collectors and institutional curators worldwide. Through his legacy, Wetherfield transformed antique clock collecting into a refined and scholarly pursuit.

* Figure based on the Bank of England Inflation Calculator

Acknowledgements

There are several books available that showcase the Wetherfield collection, particularly the work of Eric Bruton FBHI in his seminal tome, The Wetherfield Collection of Clocks, A Guide to Dating English Antique Clocks published by N.A.G. Press Ltd in 1981, has been extremely useful in researching this feature.

Hero Image: David Arthur Wetherfield (1845–1928). Artist Impression © MrWatchMaster

The next in the series The Greatest Collectors of All Time is now available on Worn & Wound.