A series of features identifying the most extraordinary mechanical masterpieces in history, blending precision, innovation, and craftsmanship. We all have our favourite timepieces either in our collection or those incredible horological masterpieces that have been invented or created through the ages. This series will showcase examples from the previous centuries up to the present day and look at the importance and impact on modern day timekeeping.

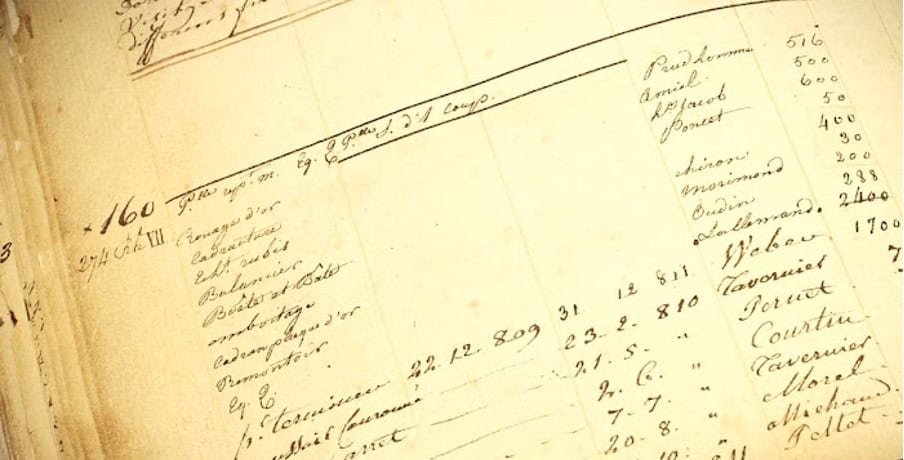

Few watches in history have captivated the world quite like Breguet No. 160, often referred to as the Marie Antoinette Watch. Commissioned in 1783, this masterpiece of horology was intended as the ultimate expression of luxury, precision, and mechanical complexity. Crafted by Abraham-Louis Breguet, the legendary Swiss watchmaker, it would take over 44 years to complete, long after Marie Antoinette’s tragic execution and Breguet’s death.

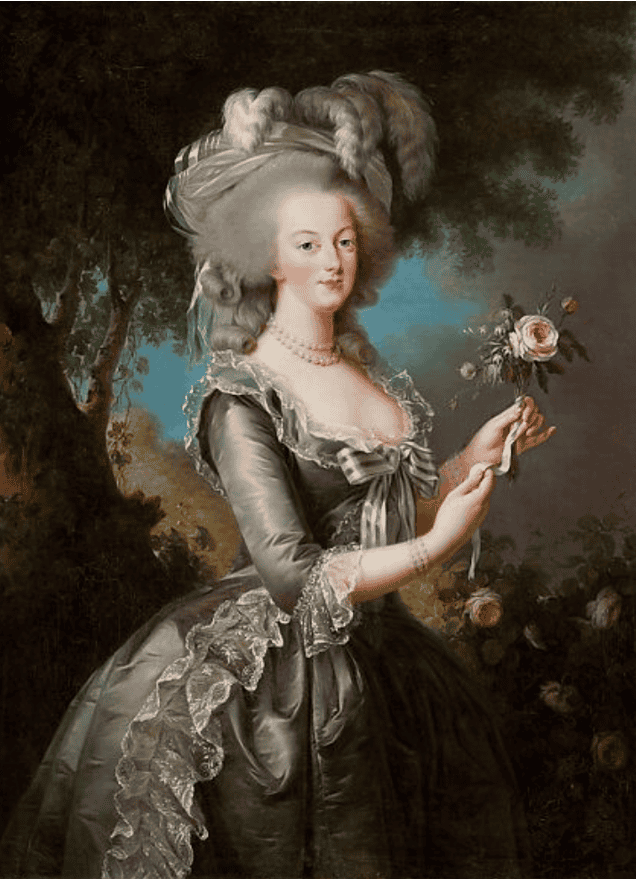

Marie Antoinette was an Austrian princess and the wife of King Louis XVI. Born on the 2nd November 1755 in Vienna, Austria, she was the 15th child of Empress Maria Theresa of Austria and Emperor Francis I, Holy Roman Emperor. She grew up in the lavish Schönbrunn Palace centre of the court of Vienna, surrounded by wealth, music, and political intrigue.

An Influential Royal Palace

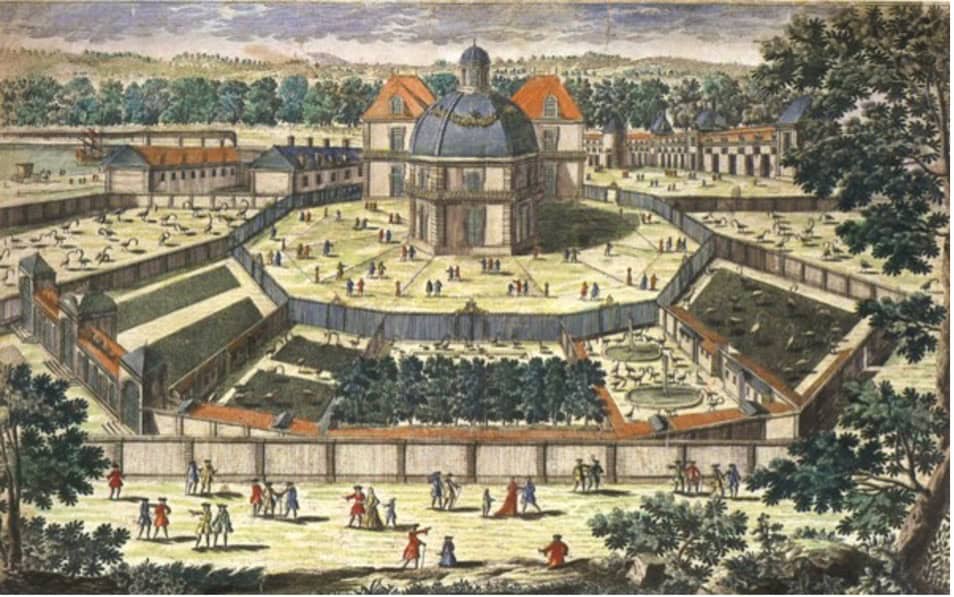

The Palace of Versailles was a major site of scientific thinking in the 17th and 18th centuries. It hosted members of the French Royal Court and included spectacular objects and animals including a rhinoceros housed in the Menagerie Royale which was Louis XIV’s first major project at Versailles (see below).

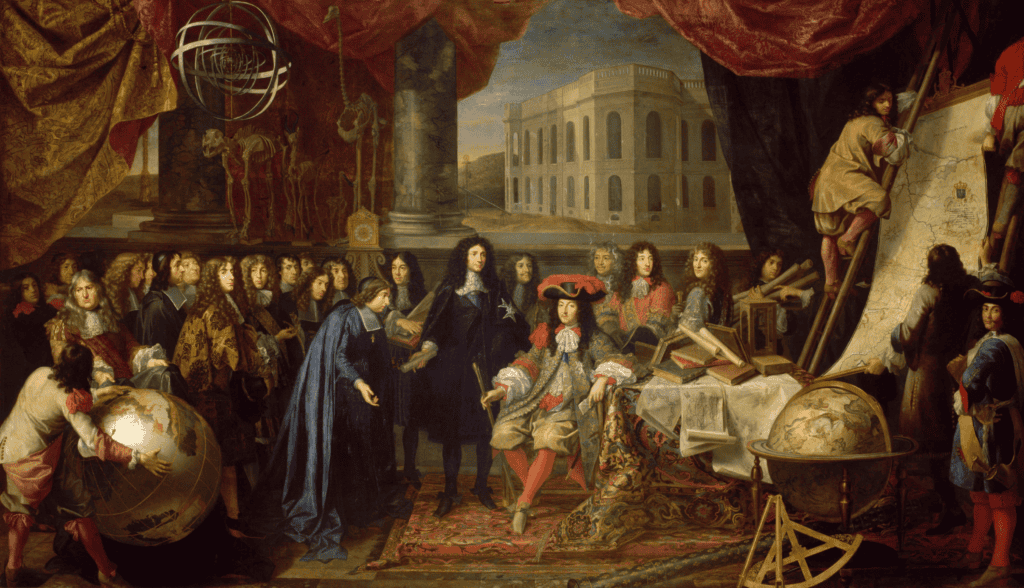

Many historically famous scientists were invited to the French Royal Court including the inventor of the pendulum for the clock, Christiaan Huygens. In 1666, King Louis XIV invited Huygens to Paris to become a founding member of the French Academy of Sciences (Académie des sciences).

Huygens (in the background of the above portrait next to the clock), worked under the patronage of Jean-Baptiste Colbert, Louis XIV’s powerful minister and continued to develop and refine his work on the pendulum and laid the foundations for more accurate timepieces. These were required for the new Observatories, charting the planets and galaxies which was becoming more important.

At the time of Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette, Huygens had already been dead for nearly a century, but his innovations, particularly in astronomy, optics, and clockmaking, continued to influence science at Versailles. The three kings closely associated with Versailles, Louis XIV, who established the palace as the seat of the French court in 1682, Louis XV, and Louis XVI, the last monarch to reside there before the French Revolution in 1789, each had a distinct connection to science that influenced Versailles, France, and the world.

They commissioned the finest scientific objects including mechanical clocks and watches, including the spring-driven bracket clock made by leading horologist, Isaac Thuret (see below).

Thuret was a renowned 17th-century French clockmaker, active during the reign of Louis XIV. He was one of the first craftsmen to work with the Dutch scientist Christiaan Huygens, who invented the pendulum clock in 1656. Thuret is particularly known for building some of the earliest pendulum clocks based on Huygens’ designs.

As one of the official clockmakers to the king, Thuret created sophisticated timepieces for the royal court at Versailles. His work played a crucial role in advancing horology (the science of timekeeping) in France, contributing to more accurate and reliable clocks that were essential for scientific research, navigation, and daily life in the 17th century.

Everything in the Palace of Versailles was of the highest quality made by the finest artisan craftsmen and women. The Queen’s bedchamber (below) was no exception, and she commissioned the ornamentalist and decorator Jean-Démosthène Dugourc to redesign it.

King Louis XVI was a known enthusiast of horology, fascinated by intricate mechanics and precision timekeeping. He personally collected, commissioned, and funded the work of some of the most skilled watchmakers of the era.

This extraordinary clock resided at Versailles and was made in Paris for Louis XV in 1754. The Clock of the Creation of the World was so ambitious that it needed the collaboration of three engineers and almost 20 years of work to make a precise astronomical pendulum with the limited techniques and materials of the 18th century.

An engraved globe of the World, the Sun, the Moon, and a representation of the Solar System. The ensemble reunited among the elements. It is supposed to give the time in every part of the world, and every celestial body used to rotate. It was restored by Vacheron Constantin in 2022 and now belongs to the Louvre Museum in Paris.

A Gift Fit for A Queen

Although never proven, the Breguet watch No. 160 was believed to have been commissioned by Count Axel von Fersen, a Swedish diplomat and rumoured lover of Queen Marie Antoinette. His ambition was to create the most advanced and beautiful watch in existence, a timepiece that would embody the Queen’s lavish lifestyle and appreciation for fine craftsmanship. At the time it was the most expensive watch commissioned for Breguet to manufacture, costing an enormous 17,000 Francs, and although it is difficult to convert into a current value in today’s money, it would have been equivalent of between $150,000 and $250,000.

The Queen was a great admirer of Breguet’s timepieces. In the 1780s, she became his most influential supporter at the French court. She owned several of his watches and eagerly promoted his work to the kingdom and distinguished guests.

Breguet, already a renowned watchmaker, was tasked with designing a watch that incorporated every possible complication available at the time. The result was a gold-cased pocket watch with sapphire crystal, featuring multiple dials and revolutionary mechanical functions.

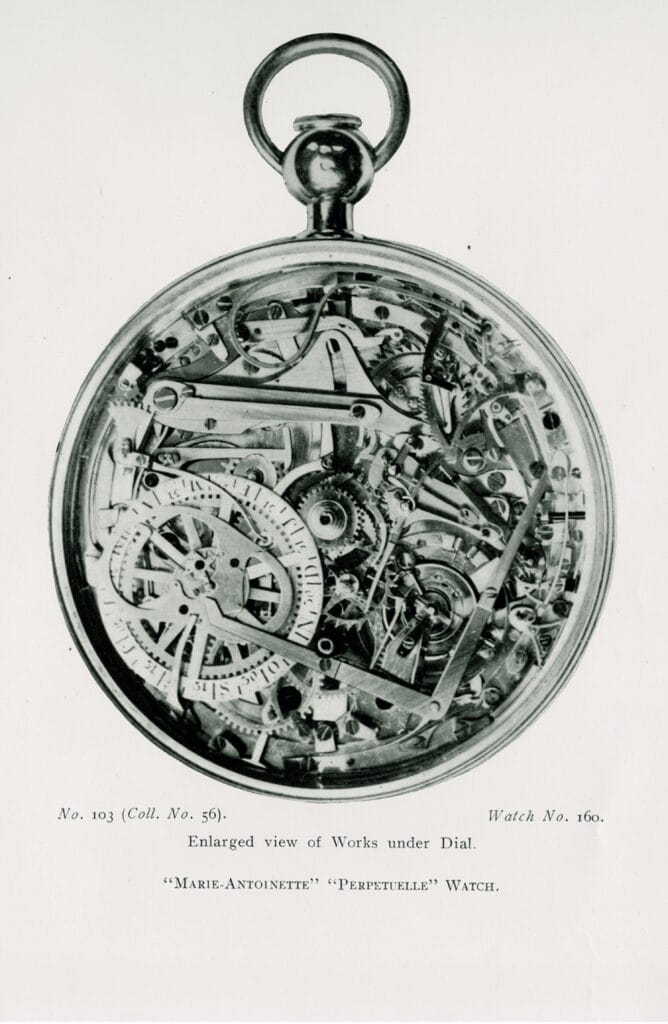

The Breguet No. 160 was designed to be the most complex and advanced timepiece of its era. In total it featured an extraordinary 23 complications, including, the major complications listed below:

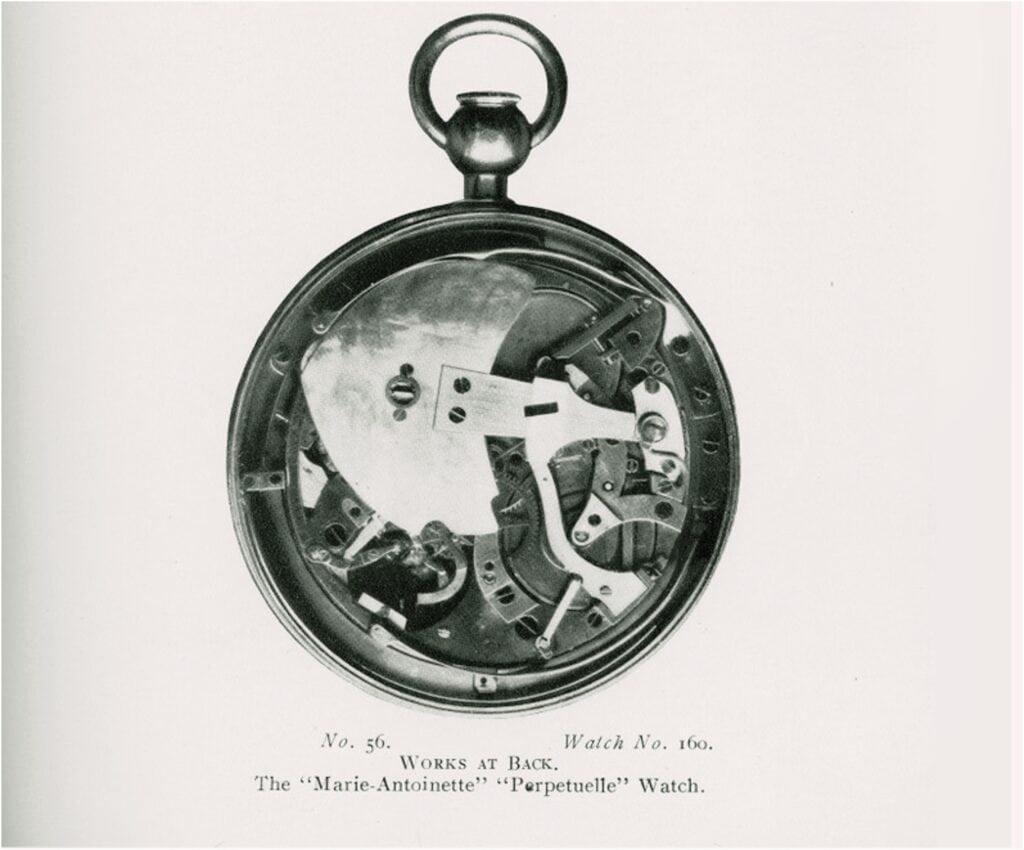

- Perpetual (Self-Winding) Mechanism – One of the earliest automatic watches, powered by the wearer’s movement (see below).

- Minute Repeater – Chimed the hours, quarters, and minutes on demand.

- Perpetual Calendar – Automatically adjusted for leap years and displayed the day, date, and month.

- Equation of Time – Showed the difference between solar time and standard time.

- Power Reserve Indicator – Displayed how much energy remained before winding was needed.

- Thermometer – Measured temperature, a rare feature in pocket watches.

- Chronograph (Stopwatch Function) – Allowed precise time measurement.

- Independent Seconds (Deadbeat Seconds) – Displayed seconds in a smooth, jumping motion.

On the 16th of October 1793, Queen Marie-Antoinette of France was led to the guillotine, a few months after her husband, King Louis XVI, so she never received the watch by the time it was completed in 1827. Despite this, the watch became a symbol of 18th-century horology, standing as a testament to Breguet’s genius.

The Breguet No. 160 was truly ahead of its time. It included features that were unprecedented in the late 18th century, many of which are still found in high-end watches today.

Breguet No.160 Disappears for 24 Years

In one of the most daring watch thefts in history, the Breguet No. 160 was stolen in 1983 from the L.A. Mayer Museum for Islamic Art in Jerusalem. The museum housed an extensive collection of timepieces, the majority bequeathed by leading Breguet collector Sir David Salomons, but the No. 160 was its crown jewel.

The thief broke in, bypassing security, and stole nearly 100 rare watches. Investigators suspected an inside job, but the case went cold for decades. Many feared that the watch had been melted down for gold, destroying a priceless piece of history. For 24 years, the whereabouts of the watch remained a mystery. Collectors speculated that it had been sold on the black market or hidden in a private collection, never to be seen again.

In 2006, an Israeli lawyer contacted the museum, claiming he represented someone with information about the stolen watches. The following year, a staggering discovery was made with many of the missing timepieces, including Breguet No. 160, returned under mysterious circumstances.

Investigators later identified the thief as Na’aman Diller, an Israeli criminal mastermind known for high-profile heists. Before his death in 2004, Diller had hidden the watches in safety deposit boxes across Europe and the U.S. His widow eventually led authorities to their location, and the watch was miraculously intact.

In 2004, while the original Marie Antoinette watch was still missing, Nicolas Hayek, then CEO of the Swatch Group, tasked Breguet’s watchmakers with creating an exact replica. Using archival records and old photos, they completed the masterpiece in 2008, naming it Breguet No. 1160 as a tribute to the original No. 160.

The watch’s self-winding movement (perpétuelle) consists of 823 finely crafted parts. Its plates, bridges, and moving components are made of polished pink gold, while screws are blued and polished steel. Sapphire bearings reduce friction, and the watch features a special escapement, a gold cylindrical balance spring, and a bimetallic balance. A double pare-chute shock protection system safeguards key components from impacts.

How Breguet No. 160 Changed Horology Forever

The influence of the Breguet No. 160 extends far beyond its historical value. It has shaped modern watchmaking, inspiring both contemporary luxury brands and independent watchmakers.

The Breguet No. 160 Marie Antoinette Watch is more than just a piece of mechanical brilliance—it is a symbol of luxury, history, and human ingenuity. From its royal commission and painstaking craftsmanship to its shocking theft and dramatic recovery, this watch has lived a fascinating and eventful life.

Today, valued in excess of $100 million, its legacy continues to influence horology, ensuring that the name Breguet remains synonymous with excellence, innovation, and timeless elegance.

I had the privilege of seeing the exquisite Marie Antoinette Watch up close and personal in the Versailles: Science and Splendour exhibition at the Science Museum in London and it was truly stunning. An experience I will remember and treasure forever.

Would Marie Antoinette have treasured this watch? We’ll never know. But what is certain is that the world of horology will forever remember the watch that was made for a Queen.

Hero Image: Watch No.160 known as the Marie Antoinette. Made by Abraham-Louis Breguet, completed in 1827. Image courtesy © MrWatchMaster

The next in the series The Greatest Horological Masterpieces of All Time is now available on Worn & Wound.