The Great Clock of Westminster, often known simply as Big Ben, is one of the most iconic landmarks in London and a symbol of the United Kingdom’s rich history and architectural brilliance. Housed in the Elizabeth Tower at the north end of the Palace of Westminster, the clock was completed in 1859 and has since become a celebrated masterpiece of Victorian engineering.

Designed by clockmaker Edward John Dent and architect Augustus Pugin, the Great Clock is renowned for its remarkable accuracy and the deep, resonant chime of its massive bell, Big Ben. Over the decades, it has stood as a steadfast guardian of British tradition, witnessing countless historic moments and continuing to captivate visitors from around the world.

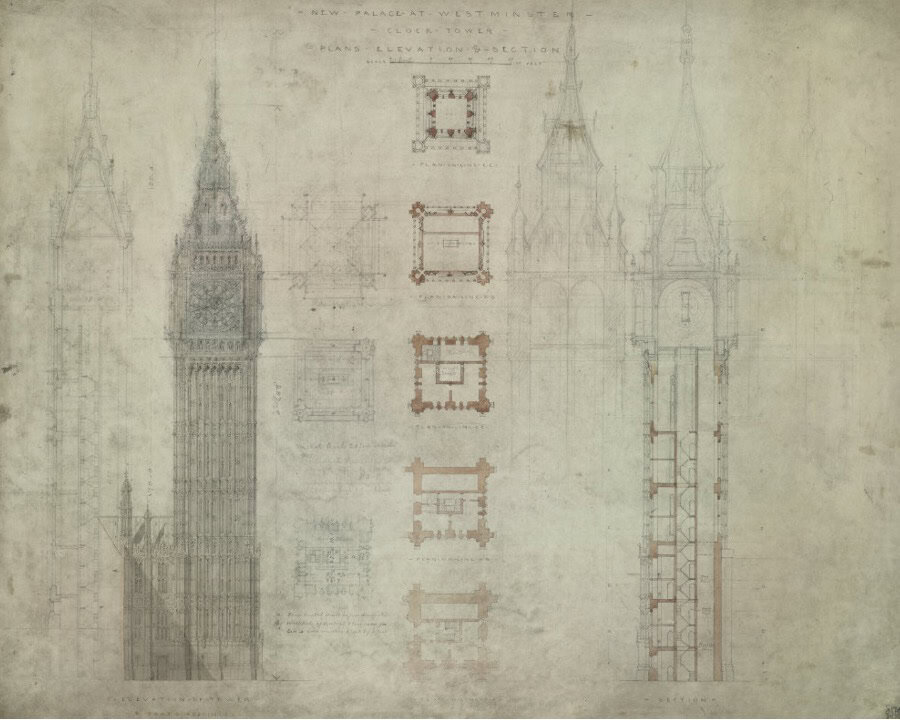

Charles Barry’s design for the Houses of Parliament did not originally include a clock tower. He was asked to include one and his first designs were added in 1836. Construction began in 1843, but the tower and its clock and great bell (Big Ben) were finished in 1859.

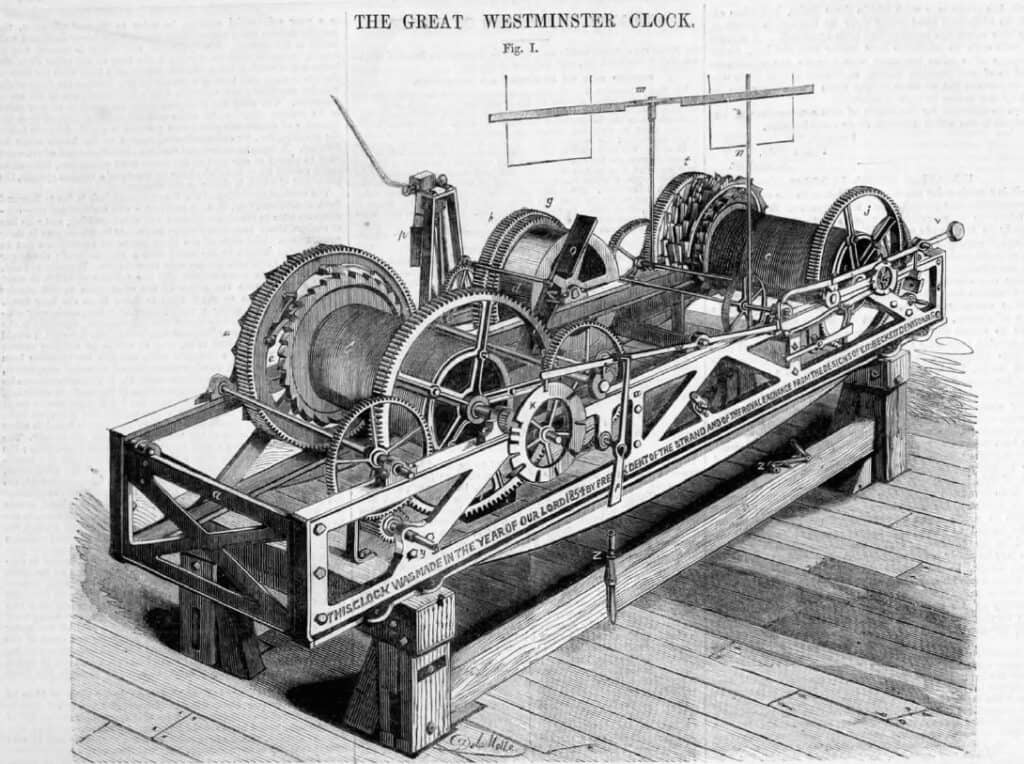

“The merit of the design of the Westminster clock is due to Edmund Beckett Denison, a gentleman who has devoted very considerable time to the study of clock and watchmaking and who has at various times introduced many important improvements in their construction.”

From a report by The Engineer paper in 1856

A Brief History of The Great Clock

The Clock Tower was renamed the Elizabeth Tower to honour HM Queen Elizabeth II’s Diamond Jubilee. The largest and most extensive conservation of the Elizabeth Tower began in 2017, taking 4-years, to preserve the clock tower for future generations.

The decision to install the Great Clock of Westminster was driven by both practical and symbolic reasons. It was deemed necessary to rebuild the Palace of Westminster after a massive fire that destroyed much of the Palace in 1834. At the time, most public clocks were often unreliable, and London needed a precise timekeeper. The new clock was required to strike the hour accurately to within one second a day, to serve as the city’s official time reference.

Before the standardisation of time (this wasn’t in place until 1852, when the timekeepers at Greenwich introduced equipment that transmitted accurate time signals throughout the country over the electric telegraph network), people relied on church clocks, personal watches, or the sun, leading to inconsistencies. The Great Clock ensured a single, reliable time reference for the city, especially for Parliament and government officials.

The chimes of Big Ben helped workers and citizens structure their day and became a symbol of British engineering and power, demonstrating Britain’s technological and engineering expertise during the 19th century.

When the BBC started radio broadcasts in 1922, they used Big Ben’s chimes to signal the time to listeners across Britain – in fact they still use them to this day. This further cemented its role as the country’s most trusted timekeeper.

The Competition to Build the Great Clock

The competition to build the Great Clock of Westminster was highly rigorous and attracted multiple contenders. The British government set strict requirements for the clock, based on specifications drawn up by Sir George Airy, the Astronomer Royal. The key requirement was that the first strike of the hour bell must be accurate to within one second of the correct time.

The public competition (1846-1851) had strict design standards and attracted bids from several leading clockmakers attempted to meet the challenge including, Benjamin Lewis Vulliamy (Royal Clockmaker), John Whitehurst & Son and Edward John Dent (the eventual winner). To this day it is see as one of the most demanding public clock projects in history.

Dent worked with amateur horologist Edmund Denison (later Lord Grimthorpe) on a trial clock that was set up at the Greenwich Observatory in 1851 to demonstrate the feasibility of achieving Airy’s accuracy requirements. Dent was formally awarded the contract, largely because of his superior mechanical design in collaboration with Denison. However, Dent passed away in 1853, and his stepson Frederick Dent completed the clock mechanism in 1854.

The Mechanism of the Great Clock

The clock mechanism was one of the most advanced of its time, incorporating a gravity escapement designed by Denison, which improved accuracy by minimising the effect of external forces like wind on the hands. The Great Clock officially began operating on the 31st of May 1859.

I was extremely fortunate to be invited to visit the Great Clock of Westminster recently which was a wonderful experience. It was a long climb to the top with 292 steps to the clock faces and 334 steps to the Belfry where Big Ben, the Great Bell, hangs. We were able to stand behind the dial which are 7 metres in diameter and made of 324 pot opal glass pieces in a cast iron frame, each one being hand blown.

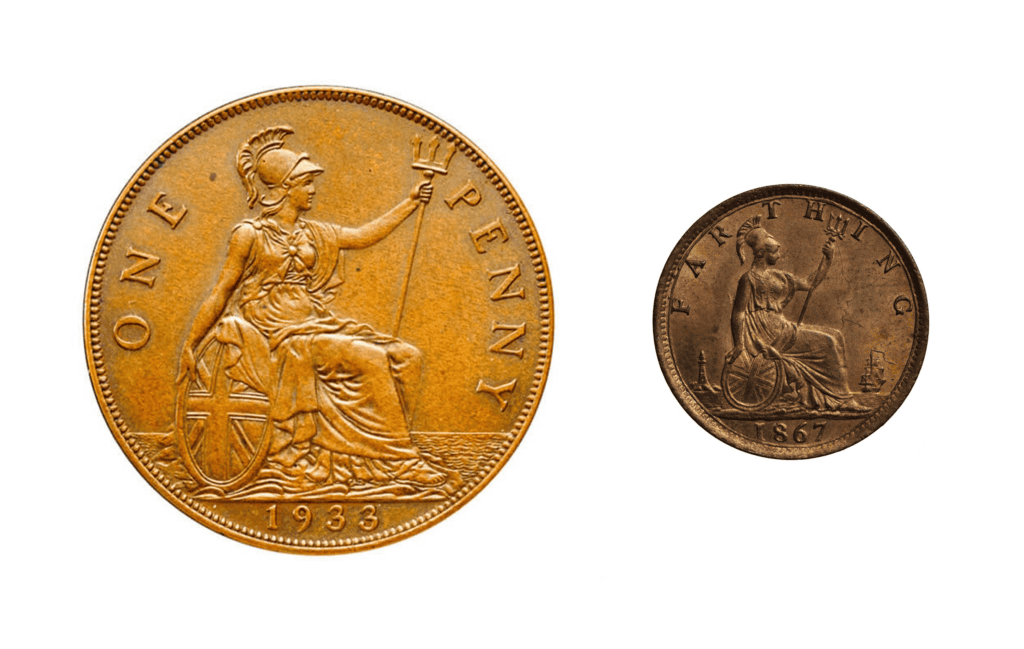

The mechanism made of cast iron weighs an astounding 5 tonnes and almost 5 metres long with each pendulum ‘beat’ lasting 2 seconds. The pendulum itself is 4.4 metres long, weighing in at 310 kg and is still adjusted using pre-decimal pennies, which in turn regulate the clock mechanism. Adding one penny causes the clock to gain two-fifths of a second in 24 hours. Today due to the advancement of technology the regulation of the clock can be managed with farthings which are a quarter of the size of the old penny piece (see below).

The huge minute hands are made of copper sheet with each hand measuring 4.2 meters in length and weighing 100 kilograms. They travel the equivalent of 120 miles a year. That’s the distance from London to Birmingham.

During the tour it was explained that the clock is used to synchronise the firing of guns for Remembrance Sunday at the Cenotaph, the national war memorial in London. They had to measure how long it took the sound of Big Ben to reach it which was 2 seconds and had to be taken into account for the ceremony that takes place every year on the 11th November at 11am to mark the Armistice that signified the end of the First World War.

Every year the military coordinates the firing of the guns from the movement room of the Great Clock of Westminster. According to legend, one year the 10-second countdown began and when they reached ‘5’ the officer mistook this for the signal to ‘fire’ which meant they were 5 seconds early. From then on, the countdown always excludes the number ‘5’ and goes down in this sequence 10, 9, 8, 7, 6, 4, 3, 2, 1 to ensure it won’t happen again.

We also learned why the Portcullis symbol is used in Parliament. When the tender for the rebuilding of the Palace of Westminster was issued in 1836, the Architects applying had to do so anonymously. To identify themselves each submission included a unique symbol so the winning designer could be identified when the contract was awarded. The winning architect for the rebuilding was Sir Charles Barry who was so taken with the portcullis as a symbol that he used it to identify his plans when they were submitted to the competition judges assessing designs for the new Palace. Augustus Pugin later used it extensively for the interior design of the Palace – it is the essence of neo-gothic and can be seen everywhere from wallpapers to chairs to carpets (see above).

The Origin of the Name Big Ben

The Great Bell of the clock at the north end of the Palace of Westminster, commonly known as ‘Big Ben’, has an uncertain origin regarding its nickname. One prevalent theory suggests that it was named after Sir Benjamin Hall, the First Commissioner of Works during the bell’s installation. According to this account, during a parliamentary debate, an MP allegedly remarked that the bell should be named ‘Big Ben’ in Sir Benjamin Hall’s honour. However, unfortunately this specific comment is not recorded in Hansard, the official transcript of Parliamentary debates, so cannot be substantiated.

Another theory is that it was named after Benjamin Caunt, a famous and physically imposing English bare-knuckle boxer of the time. He was often referred to as ‘Big Ben’, and the name may have been used as a popular cultural reference. Though no official record confirms which theory is correct, the Sir Benjamin Hall explanation is the most commonly accepted.

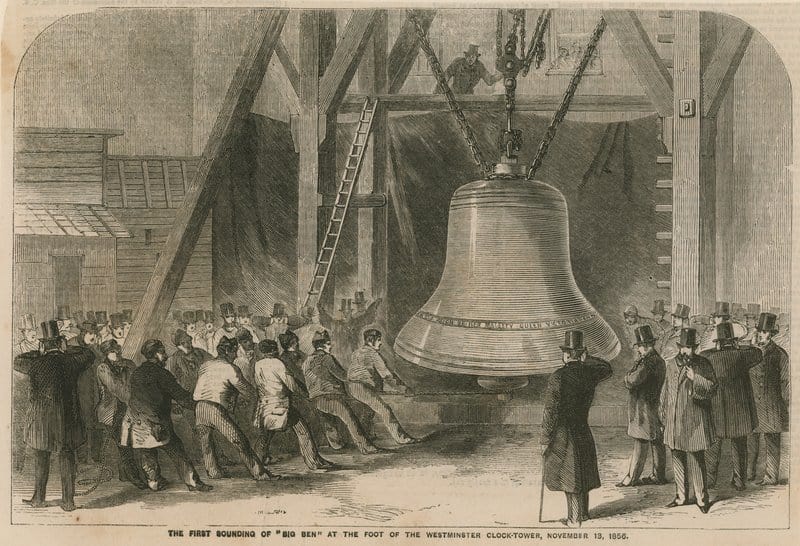

The bell was cast in 1856 and first chimed on 11 July 1859. Given the lack of detailed records from that period, pinpointing the exact instances when the Great Clock or Big Ben was mentioned in Parliament is challenging but being in the presence of the bell was very special and very loud. I was in the belfry at midday, so heard the distinctive sound of Big Ben up close and personal. You could also feel the bell striking, as it resonated through the tower, which was an interesting experience.

Big Ben is not the only bell in the clocktower. There are four other bells in the Belfry that are fixed and struck by hammers from outside, rather than swinging and being struck from inside by clappers. Big Ben is the heaviest at 13.7 tonnes and their notes all combine to form the famous tune.

The Great Clock Remains a Cultural Icon

The Great Clock is iconic – or more likely Big Ben – has captured the imagination of the country, indeed the world. The clocktower has played a starring role in artwork, books, film and television. From children’s tales to action thrillers, Monet to modern art, Big Ben offers something for everyone, even taking pride of place of the HP Sauce bottle for decades. It is no wonder that it was the most instagrammed tourist attraction in the United Kingdom (reported by The Sun in 2017).

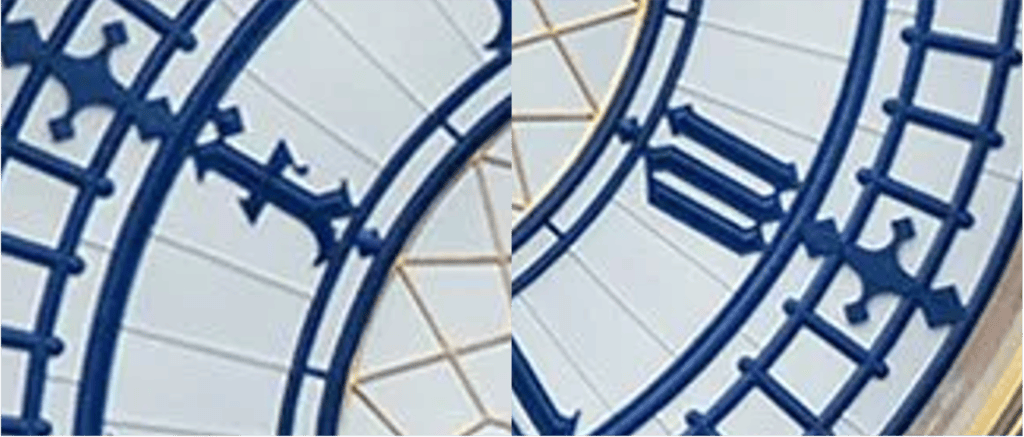

There are still many things that fascinate people all over the world. A good example being the design of the dial by leading architect of the age, Augustus Pugin. Look closely at the numerals which you may believe to be Roman, however, Pugin wanted to make his mark and substituted the ‘X’ for a stylised ‘F’ and he also changed the ‘IIII’ to ‘IV’ at 4 o’clock (see below).

Admired across the globe, the Great Clock of Westminster was more than just a functional timepiece; it became a national symbol of reliability, governance, and British engineering excellence – and still is today. Its chimes continue to mark key political moments and provides a sense of continuity in British life.

Hero Image: Dial of the Great Clock of Westminster designed by Augustus Pugin

The next in the series The Greatest Horological Masterpieces of All Time is now available on Worn & Wound.