In this occasional series, we will explore the life and achievements of the greatest and most respected horologists of their time. In the great tapestry of English horology, certain names shine brightly for their ingenuity, craftsmanship and enduring influence, and among them stands Benjamin Gray. He was a master watchmaker whose precision and artistry helped define the golden age of 18th-century English watchmaking.

Gray is first recorded working in St. Martin’s-in-the-Fields in 1716, establishing himself at the very heart of London’s thriving horological community. By 1752, his success saw him relocate to 74 Pall Mall – an address befitting a craftsman of growing stature and reputation.

Renowned for producing fine quality clocks and watches of exceptional refinement, Gray’s reputation reached the highest levels of society. In 1743, he was appointed Watchmaker in Ordinary to the King, a prestigious honour that confirmed his standing among the elite makers of his generation.

That same year marked another significant chapter in his career when he entered into partnership with François Justin Vulliamy, uniting two respected names in a collaboration that would further strengthen his influence within London’s watchmaking circles.

An innovator as well as a master craftsman, Gray was also probably the first maker in London to produce pedometers, a reminder that his interests extended beyond traditional timekeeping into the broader world of precision instrumentation.

A Watchmaker In The Age Of Discovery

Benjamin Gray was active during a period when London was the beating heart of horological innovation. The 18th century was an era shaped by exploration, science and an insatiable desire to measure time more accurately than ever before. Britain’s naval dominance and expanding global trade demanded increasingly reliable marine timekeepers.

Gray rose to prominence in this vibrant and competitive environment. Working in London, he built a reputation for exceptional quality and refinement. His workshop produced longcase clocks, bracket/table clocks and watches that were admired not only for their technical excellence but also for their aesthetic harmony.

This is a remarkable gold pair-cased repeating watch by Benjamin Gray, London, circa 1730 (above). The sumptuous gold outer case is adorned with a finely executed repoussé head of Apollo (below), the god of light and the passage of time and fitted with a watch glass. Within, the inner plain gold case has had its bezel and glass removed so that it fits, rather tightly, inside the outer shell. Both cases carry London hallmarks for 1730, firmly anchoring the piece in the golden age of English watchmaking.

The white enamel dial is elegantly restrained, fitted with a steel hour hand (the minute hand now absent) and wound directly through the dial, a charmingly practical feature of the period. At its heart beats a movement equipped with a verge escapement, enhanced by a diamond end-stone and silver rim cap, details that speak to refinement as much as reliability. The watch is further fitted with a dumb repeater, striking via a single hammer. The movement is signed ‘Benjamin Gray London r.s.c.’ a subtle yet powerful reminder of the master behind this exceptional timepiece.

Master Of Craft And Precision

Gray partnered with Justin Vulliamy, a very talented Swiss emigre watchmaker who married Gray’s daughter and was his business partner from 1743 to 1760 at Gray’s premises in Pall Mall. Gray is perhaps best remembered for his association with the development of marine timekeeping.

Graham had been a close associate of Thomas Tompion, often referred to as the “Father of English Clockmaking”. In this lineage of mastery, Gray inherited both technical insight and a relentless pursuit of accuracy.

Gray’s craftsmanship was meticulous. His movements were beautifully finished, with finely executed engraving and elegant dial work. The proportions of his cases reflected the restrained sophistication typical of the finest London makers of the period.

Reputation And Royal Connections

Gray’s standing within London society was considerable. His work was sought after by discerning clients who valued both precision and prestige. Fine English clocks of the era were statements of intellect and status, and Gray’s pieces embodied both.

His instruments were not merely timekeepers; they were objects of scientific and artistic significance. Each represented the pinnacle of what skilled hands and disciplined minds could achieve in an age before industrialisation.

A Legacy Of Quiet Influence

Unlike some of his contemporaries, Benjamin Gray did not leave behind a single revolutionary escapement or mechanical breakthrough bearing his name. Instead, his legacy lies in the standard of excellence he maintained and in the influence he exerted behind the scenes.

By supporting innovation, upholding uncompromising craftsmanship and operating at the highest levels of London’s horological community, Gray helped shape the trajectory of precision timekeeping in Britain.

Today, surviving clocks and watches signed by Benjamin Gray are treasured by collectors and museums alike. They stand as reminders of a period when the measurement of time was both a scientific frontier and a fine art.

In the pantheon of great horologists, Benjamin Gray deserves recognition not only as a master craftsman, but as a pivotal figure in the network of brilliance that defined 18th-century English watchmaking.

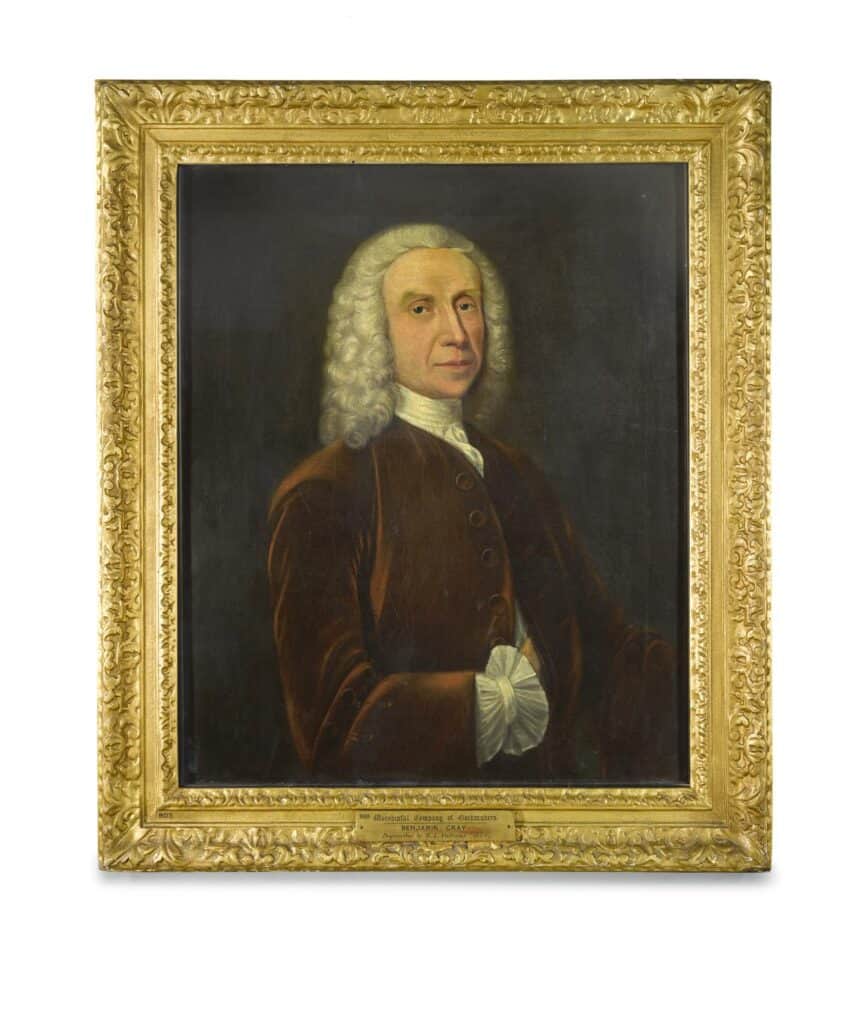

Hero image: Portrait of Benjamin Gray (1676 – 1764), oil on canvas, attributed to J. Davison, mid 18th century. Courtesy of The Clockmakers’ Museum/Clarissa Bruce © The Clockmakers’ Charity