In this occasional series, we will explore the life and achievements of the greatest and most respected horologists of their time. This feature will focus on Benjamin Vulliamy, Royal Clockmaker to King George III, was the son of François-Justin Vulliamy, a distinguished Swiss-born watchmaker who had made London his home. Inheriting not only his father’s Pall Mall workshop but also his maternal grandfather’s (Benjamin Gray) established business, Benjamin continued a dynasty that defined British horology at the dawn of the nineteenth century.

Vulliamy served the monarch with an artistry that fused engineering precision and sculptural grace. Yet, as his son (Benjamin Lewis Vulliamy) later observed, he was “too much of a gentleman to make a good tradesman.” The remark, affectionate though it was, captures something essential about Benjamin’s character — a man driven as much by refinement and intellectual curiosity as by commerce.

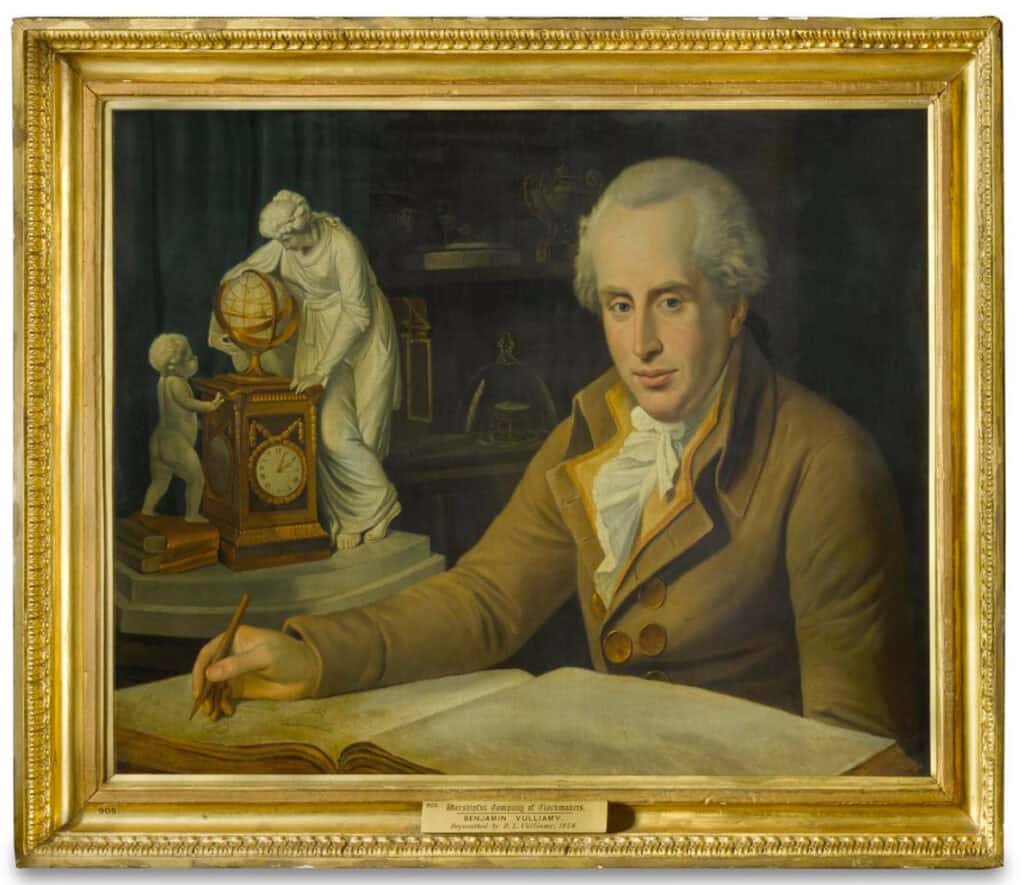

His portrait reveals this duality: a poised figure surrounded by examples of his taste — fine ormolu mounts, stately mantel clocks, and impeccably crafted watches that adorned royal rooms and aristocratic salons alike. But Vulliamy’s ambitions reached well beyond the dial. Ever the innovator, he was among the first to sink an artesian well on his Notting Hill estate — a testament to the same spirit of ingenuity that defined his approach to time itself.

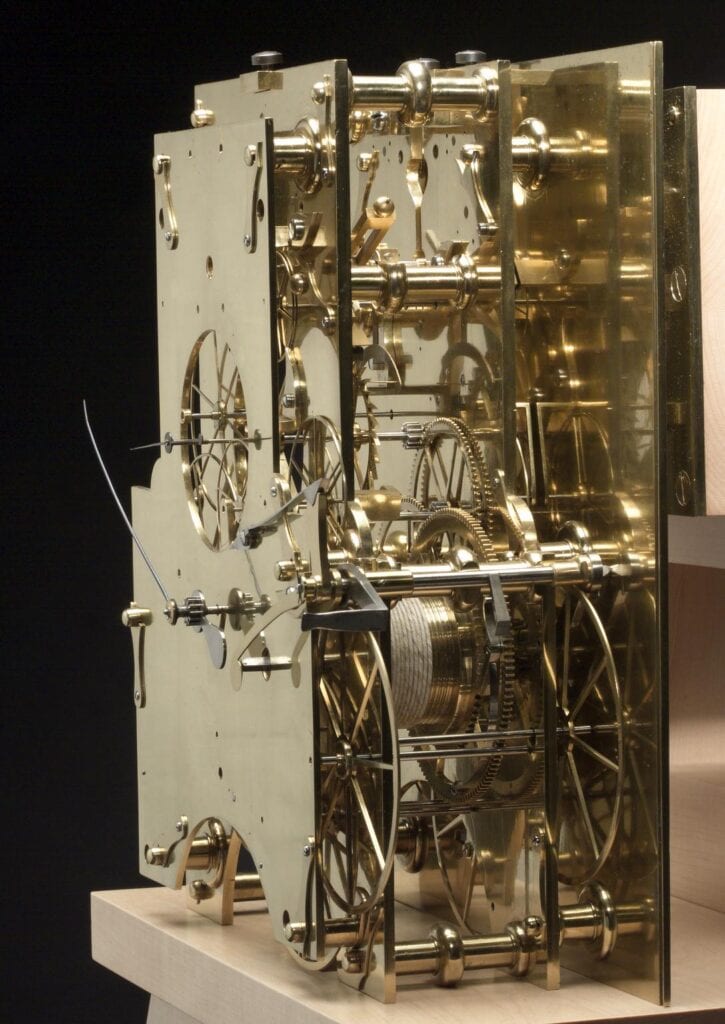

The magnificent Regulator clock (above) made by Benjamin Vulliamy for King George III in London c.1780 was used at the King’s Observatory at Kew. A regulator clock is a highly accurate timepiece, used for making precise measurements in conjunction with astronomical observation. The clock has a polished mahogany case, with a side plate and glass top for case. Rollers act as the bearings for the wheelwork, reducing the friction and the need for lubrication. For similar reasons the clock was also fitted with the grasshopper escapement that was invented by the pioneer of the chronometer, John Harrison (1693-1776). Harrison’s gridiron pendulum was also incorporated to ensure that the clock kept excellent time by compensating for changes of temperature.

Every Vulliamy clock was a combination of materials and mathematics. He fused British mechanical genius with the Continental grace inherited from his father’s Geneva roots.

His pieces were marvels of both design and craftsmanship — gilded bronze mantel clocks, ormolu-mounted timepieces, and neoclassical masterpieces incorporating marble, porcelain, and mythological figures such as the one detailed below.

This superb Royal George III ormolu-mounted white marble temple clock (No. 202) was made by Benjamin Vulliamy and delivered to the to George, Prince of Wales (1762-1830), the Prince Regent and later King George IV, on the 18th of February 1811. The Derby biscuit porcelain figure is possibly moulded by Anthony Sartine and made c.1790.

With an eagle cresting flanked by recumbent ormolu lions, added in the early Regency period, above a circular enameled clock face with Roman numeral dial and supported by a Classical portico inset with engraved ormolu panels and enclosing a Derby biscuit figure of Hygeia standing beside a pedestal with fruit on a stepped base. The the Regency embellishments of the eagle finial and recumbent lions were added specifically for the Prince Regent.

Another, adorned with figures of Mercury and Apollo, now resides in the Royal Collection — a testament to an age when clocks were not only instruments of time, but declarations of taste.

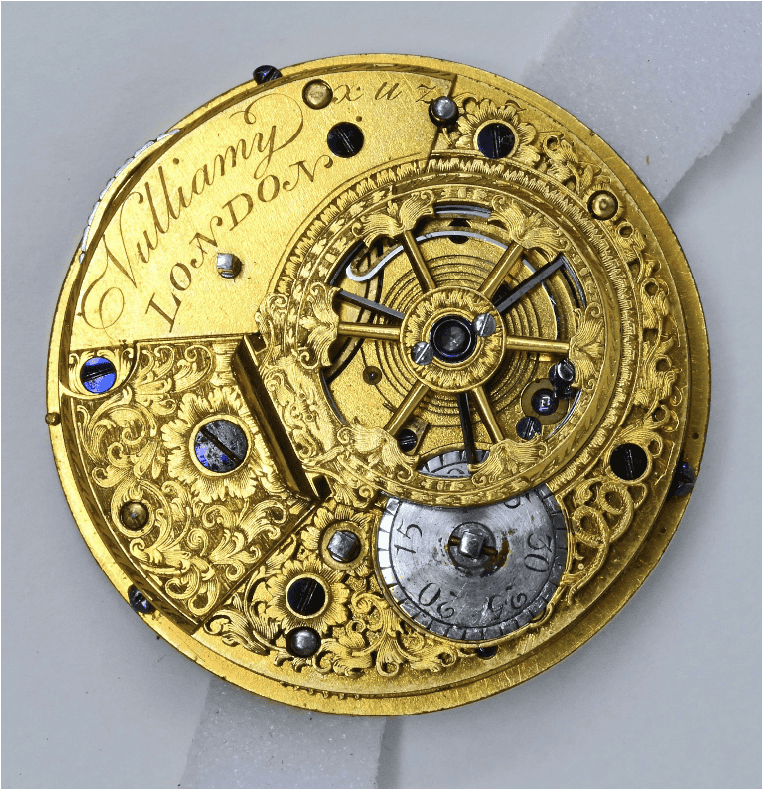

Vulliamy’s partnership with artists such as Robert Adam, John Flaxman, and Matthew Boulton brought sculpture and engineering into harmony. There was a huge demand for Egyptian objects due to a surge of interest sparked by European travellers and, most significantly, the Napoleonic invasion of Egypt in 1798, which led to a craze for all things Egyptian. This is clearly demonstrated by the above clock, which is signed ‘VULLIAMY LONDON No 438’. The Vulliamy account book describes No. 438 as an Egyptian ornamented clock. His workshop was a microcosm of Georgian collaboration and included modellers, casters, gilders, and engravers working under his exacting supervision.

Beyond his royal duties, Benjamin Vulliamy was a public advocate for precision. A Fellow of the Royal Society of Arts, he lectured on timekeeping and introduced refinements to escapements, temperature compensation, and pendulum regulation. He also served as Master of the Worshipful Company of Clockmakers in 1780.

In his year as Master, he famously protested the flood of cheap imported French clocks, arguing before Parliament that British horology must be protected and celebrated. His words were less about economics than about artistry as he feared that the work of English craftsmanship might be drowned by mechanical practices.

Benjamin trained his son Benjamin Lewis, who would succeed him as Royal Clockmaker and continue the family’s impeccable tradition well into the Victorian era. But it was the elder Benjamin who defined the firm’s character: scholarly, inventive, and immaculately English in execution.

Hero Image: Portrait of Benjamin Vulliamy (1747 – 1811), oil on canvas, late 18th century by an unknown artist. The Clockmakers’ Museum/Clarissa Bruce © The Clockmakers’ Charity