Time Through the Ages is a four part series commissioned by Worn & Wound, a place to discover watches and experience enthusiasm. In this fourth and final installment of the series, Andrew examines the dramatic leap forward in watch manufacturing made by the Waltham Watch Company, and how the Swiss watch industry responded.

“Had the Philadelphia Exhibition taken place five years later, we should have been totally annihilated without knowing whence or how we received the terrible blow. We have believed ourselves masters of the situation, when we really have been on a volcano.”

Edouard Favre-Perret, Swiss Member of the International Jury

Have you ever heard of Jacques David or Theophilus (Théodore) Gribi? How about Ambrose Webster? They were the key protagonists in the fascinating story of the rise of American watchmaking and subsequent potential demise of Swiss watchmaking. It’s a story of industrial espionage and spying that changed the course of the global watch industry forever.

The Centennial Exhibition of 1876 took place in Philadelphia and was the first official World’s Fair to be held in the United States, celebrating the 100th anniversary of the signing of the Declaration of Independence in Philadelphia. Almost 10 million visitors attended the exposition, with 37 countries participating.

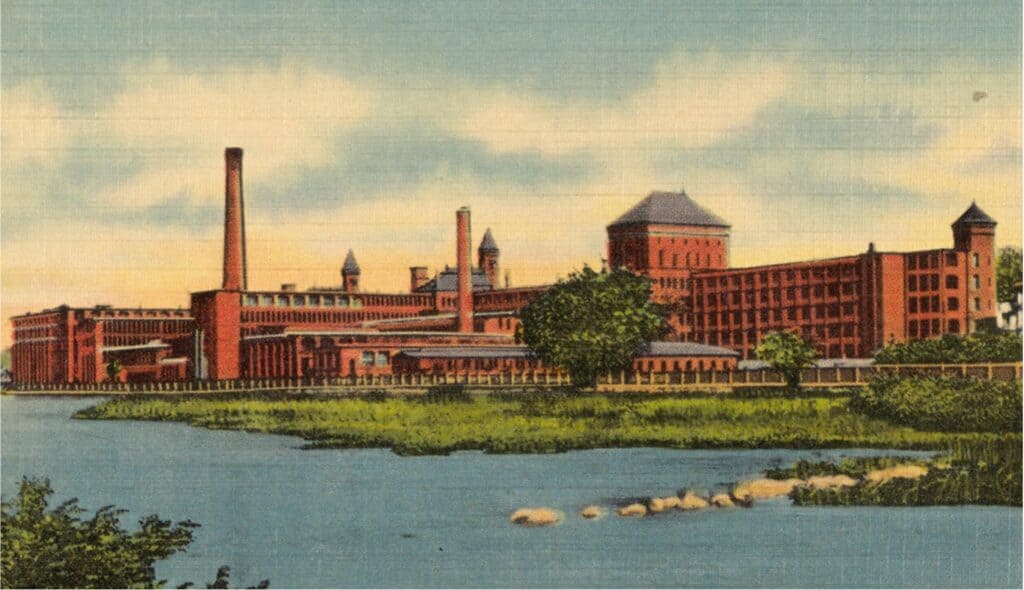

By the second half of the nineteenth century, the Waltham Watch Company transformed the entire global watch industry by introducing modern production, marketing, and sales techniques to an otherwise artisanal way of working. The company was founded by Aaron Dennison, a watchmaker born in Freeport who had been in the watchmaking business from the age of 18 years old. Originally named the American Watch Company in 1850, nine years later it was renamed as the Waltham Watch Company.

It was during the Exhibition that Waltham demonstrated the new machinery that powered the production of watchmaking that made the world ‘sit up and take notice’. Initially the success of the Waltham Watch Company at the Centennial Exhibition highlighted the shift in technological leadership in watchmaking from Europe to the United States. It underscored the capability of American companies to produce high-quality, reliable timepieces at scale.

They showcased their timepieces, emphasising the precision and craftsmanship that characterised American watchmaking. Their display included a wide variety of watches, from simple models to highly intricate and luxurious pieces (see below). The company’s presentation earned them numerous accolades, including the highest award for watchmaking. The precision and reliability of Waltham watches impressed both the judges and the public, cementing their reputation as leaders in the industry.

The exposure from the Centennial Exhibition significantly boosted Waltham’s brand recognition and market presence. The international audience, which included potential buyers and distributors, was introduced to the quality and innovation of American watchmaking through Waltham’s products.

One of the standout features of the Waltham display was the demonstration of their advanced manufacturing processes. The company was a pioneer in the mass production of watches using interchangeable parts, a technique that eventually revolutionised the watch industry. Their display highlighted the efficiency and precision of their manufacturing techniques, which at the time were ahead of many of their European counterparts.

Perhaps, one of the most ‘disturbing’ machines according to Theo Gribi, a judge at the World’s Fair from Switzerland, was Waltham’s proprietary automatic screw-making machine. The robot-like machine could produce a tiny screw every five seconds. That equates to around 10,200 per day.

He realised that having this type of technology could be a ‘game changer’ and impact negatively on the Swiss watchmaking industry. He also witnessed another noteworthy aspect of Waltham’s exhibit, namely the overwhelming presence of women employees. It was clear that the capabilities and appearance of the Waltham exhibit were no accident. What the Swiss delegation quickly recognised was the potentially dire situation for the Swiss watch industry.

The backdrop leading up to the 1876 Exhibition covers the period known as The Panic of 1873, which resulted in a global depression, the worst of which was between 1873 to 1879. Exports of Swiss watches declined suddenly from 366,000 in 1872 to 75,000 by 1876. During this time Waltham was making huge technological advances and growing.

It was at this time that the Swiss watchmakers’ professional society decided to send an expert to join Theo Gribi. This expert was Jacques David, who was technical director of Longines and related to Ernest Francillon, the Manager of Longines in Switzerland. He had specific instructions to “make a serious and detailed report of the organisation, tools, financial situation and in general any other aspect of American watch factories.”

Basically, he was being asked to become a spy for the Swiss watch industry, or more formally, the Intercantonal Society of Jura Industries (SIIJ). He was an excellent candidate, as he was an early advocate of using machines to produce watches and served as an engineer, making him a natural and convenient choice. Ultimately, Gribi and David were charged by their fellow Swiss watchmakers to acquire the secrets of America’s technology sector – the American watch industry.

They used classic espionage techniques, including disguises, recruitment of ‘agents’, such as Ambrose Webster, which culminated in a 130-page report which remained out of public view for over 125-years. Published in 1992, Rapport a la Société Intercantonale des Industries du Jura sur la fabrication de l’horlogerie aux Etats-Unis, was translated in 2003 by Richard Watkins with the permission of the Longines Watch Company. It is probably the most important document in the history of modern watchmaking and a summary is available for download here.

The emergence and exponential growth of the Swiss watch making industry can be linked back to the time of the presentation of the report to the Intercantonal Society of Jura Industries (SIIJ). It gives us a fascinating insight into the hugely competitive world of watchmaking in the final quarter of the 19th century.

A new series, The Greatest Horological Inventions of All Time is now available on Worn & Wound. In the first instalment, we look at the pendulum clock, an invention largely taken for granted today, but one which led to virtually every horological advancement commonly known.