Time Through the Ages is a four part series commissioned by Worn & Wound, a place to discover watches and experience enthusiasm. In this second instalment we examine the life and career of Abraham-Louis Breguet, inventor of the tourbillon and many other important watchmaking advancements.

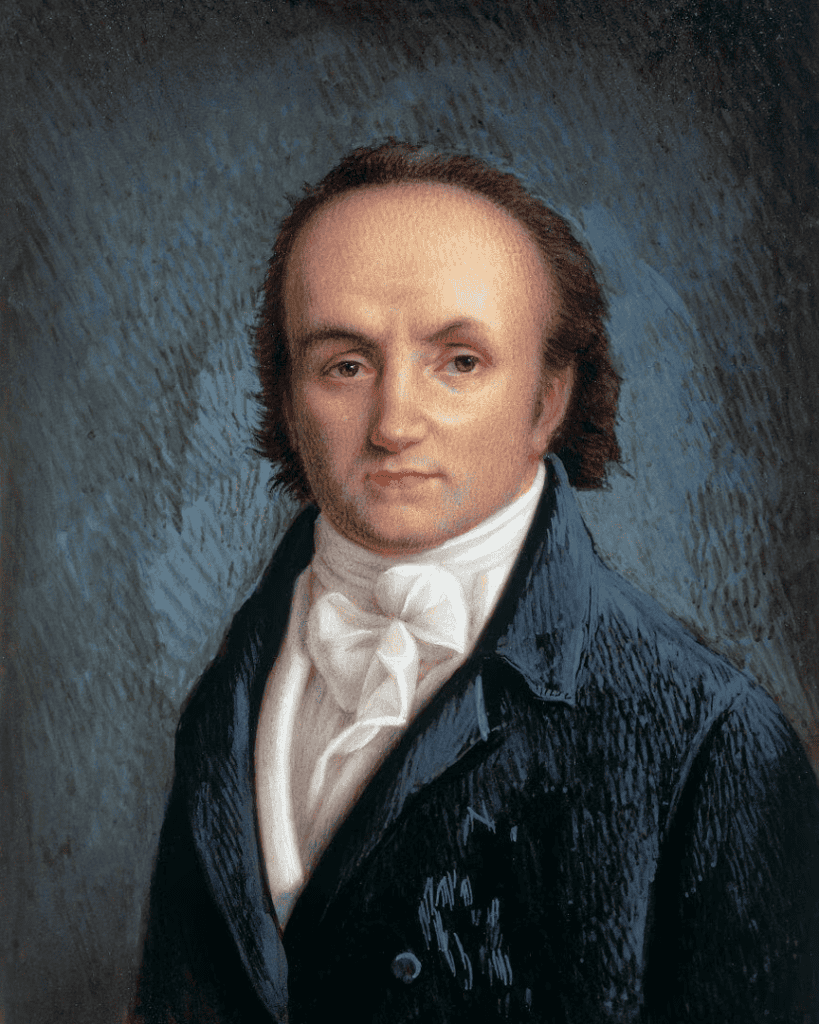

Abraham-Louis Breguet (1747–1823) was a designer, inventor, and watchmaker. Being a master craftsman in the field of watchmaking earned him a prestigious clientele that included Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette, alongside other international nobility, and the elegance and technical innovations of his designs were considered the height of style and fashion.

Breguet was born in Neuchâtel on the 10th January 1747, but it was in Paris that he spent most of his productive life. He is credited with the development of the successful self-winding perpétuelle watches, the introduction of the gongs for repeating watches, the first shock-protection for balance pivots and of course the tourbillon. Every watch that left his workshops demonstrated the latest horological improvements in an original movement, mostly fitted with lever or ruby-cylinder escapements that he perfected.

He was a great entrepreneur and marketed his magnificent watches brilliantly. Perhaps his most valuable market was England. Breguet left Paris in a hurry around 1793 as he was caught up in the unrest which led to the French Revolution and was apparently marked for the guillotine, possibly because of his association with the Royal Court. Thankfully, safe passage was arranged that enabled Breguet to escape to Switzerland (although it remains unconfirmed, it was thought he disguised himself as a woman), from where he travelled to England.

His English clients read as a ‘who’s who’ of Georgian Britain, and during the late 1700s, he visited London several times, becoming friends with one of the country’s finest chronometer makers, John Arnold, and later recruited English craftsmen to work for him in France.

Tourbillon Invention

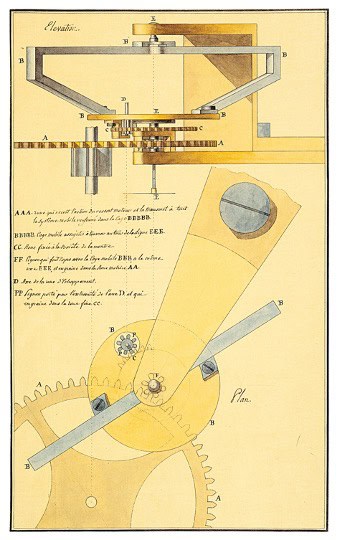

During the final decade of the 18th century, watchmakers tried to tackle the influence of temperature and gravity which both affected the accuracy of pocket watches. To some extent, the practical issues with temperature had been addressed by John Harrison with the use of a bi-metallic balance – made of both steel and brass. Breguet realised that the key to solving the problem of gravity was to take gravity out of the equation by placing the entire escapement system into a rotating cage. The development of the ‘tourbillon’ (translated as ‘whirlwind’) began around 1793, and on 26 June 1801 a patent was granted, valid for 10 years.

“To carry a fine Breguet watch is to feel that you have the brains of a genius in your pocket.”

Sir David Salomons Bt

The English Connection

Breguet produced many exceptional timepieces, namely, pocket watches, clocks, marine chronometers, and items of a scientific nature, including thermometers. Perhaps his finest work was reserved for his best clients, many living across the Channel in England. Although the watch made in honour of Queen Marie-Antoinette, watch number 160, is often noted as his most exquisite, I would argue that the Breguet No. 666 Pendule Sympathique is in the same sphere with regards to genius, and probably the most complicated clock in the world when it was sold in 1814.

“I have invented a means of setting a watch to time, and regulating it, without anyone having to do it. The most coarsely made watch, provided it does not stop, will serve its owner as though he had a garde temps. This is how it works: you have a second clock or a marine arranged to receive the watch. Every night on going to bed, you put the watch into the clock. In the morning, or one hour later, it will be exactly to time with the clock. It is not even necessary to open the watch.”

Abraham-Louis Breguet, letter to his son, Louis Antoine, 1795

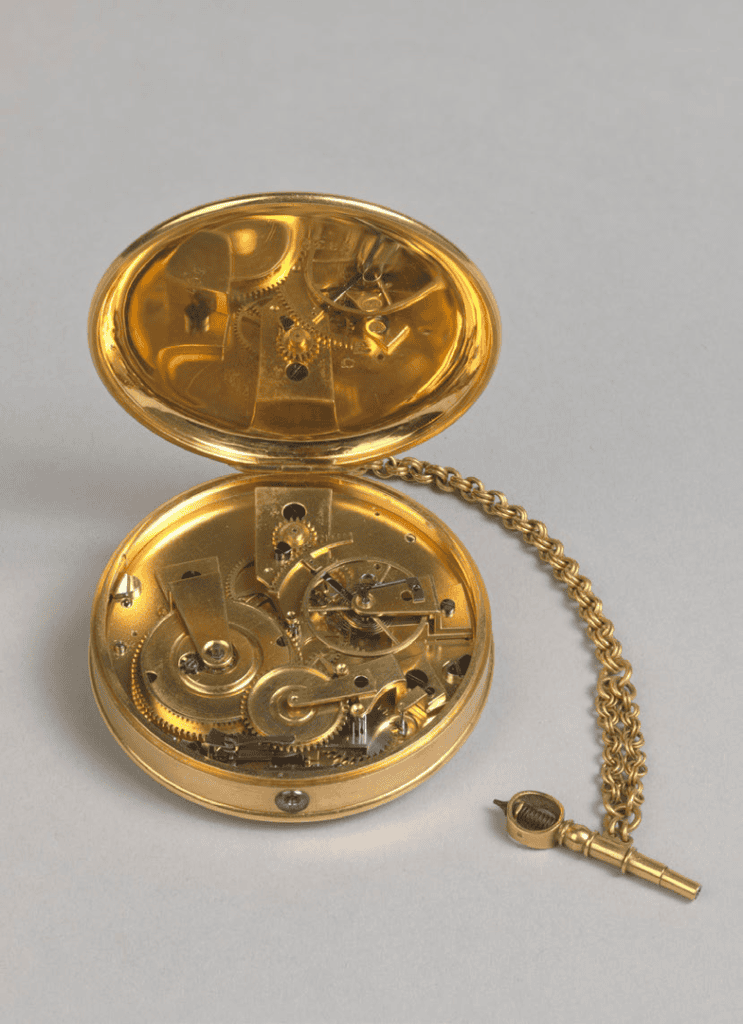

Although described by Breguet as a pendule Sympathique, the work of synchronisation in Breguet No. 666 is done entirely by the watch. The sole purpose of the clock is to perform accurately and, every twenty-four hours, trigger the setting and regulating mechanism in the watch. The original Sympathique clock (invented by Breguet in 1793) did the opposite, by automatically setting and winding the watch daily when placed into the recess at the top of the clock.

The movement inside Breguet No. 507 is a L’Epine calibre with single going barrel, ruby cylinder escapement, uncompensated brass balance and blued steel balance spring without terminal curve. Breguet’s use of an uncompensated balance and cylinder escapement would seem to be a deliberate choice in order that the working of the Sympathique mechanism may be readily observed. This watch and its companion clock (No.666) were originally supplied to the George IV when Prince Regent for his London residence, Carlton House, and remain in the British Royal Collection.

Perpetual Motion

Although it was Abraham-Louis Perrelet who is credited with inventing the self-winding watch movement, he sold some of his watches to Breguet who went on to improve the mechanism in his own version of the design, calling his watches ‘perpetuelles’, the French word for perpetual.

The movement of Breguet No. 3759 is a typical Breguet perpétuelle layout with two going barrels, lever escapement, bimetallic balance, helical blued-steel balance spring and Breguet’s suspension élastique shock protection. It is wound by a platinum weight pivoted on the backplate. It also has a minute repeating mechanism under the dial striking on two

gongs. It was sold in 1821 to Mr. Henry Perkins (A noted collector and Partner in the London brewing company Barclay, Perkins & Co) for 5,000 francs.

Interesting Inventions

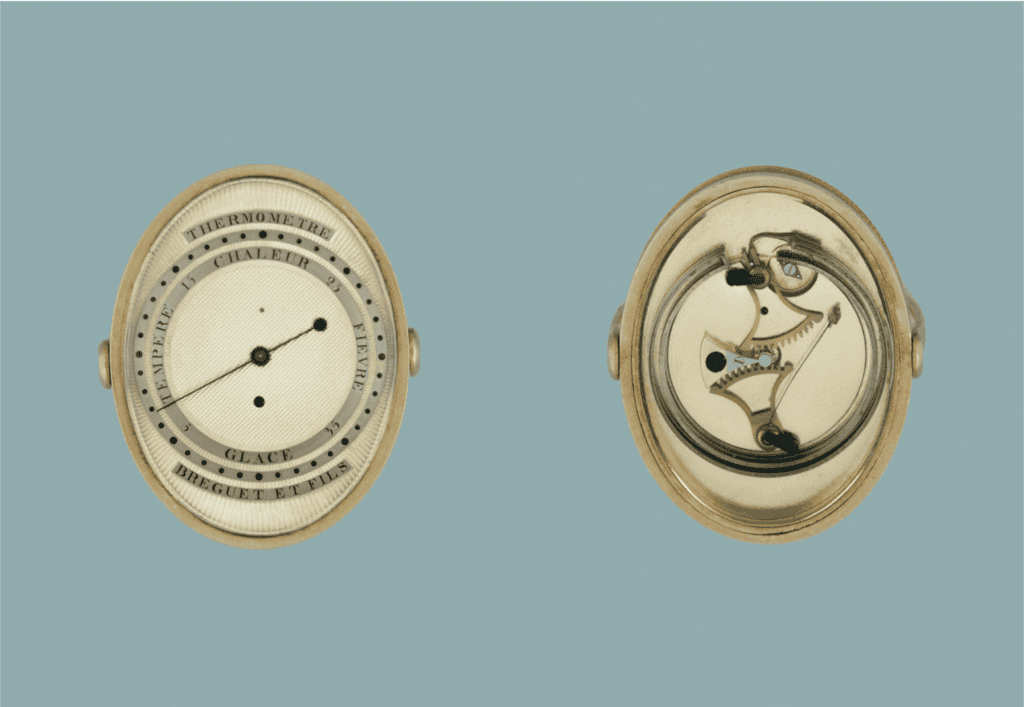

Breguet devoted considerable time to developing the thermometer but produced very few, the ninth was sold to Prince Antonio of Spain in 1813 (See Breguet – Watchmakers since 1775 by Emanuel Breguet, page 263).

The ring thermometer’s indicating hand is attached to the arbor of a pinion which engages with two brass racks. A bi-metallic strip in the form of a double ring is connected to one of the brass racks. A rise in temperature causes the bi-metallic strip to curl inwards, with a fall in temperature the strip uncurls.

A Magnificent Watch for A King

This exceptionally rare gold four-minute tourbillon watch (see main image) was made for George III in 1808. This cutting-edge pocket watch was ordered for the King who had a great interest in the sciences and had his own collection of instruments in his private observatory at Kew. This was at a time when England was at war with France, and bears the signature of Breguet’s London agent, Louis Recordon, perhaps to disguise its French origins at the time.

This exquisite timepiece features a gold case and dial with multiple contrasting finishes and blued steel moon hands and includes the rare feature of a thermometer for a watch. It is labelled as a ‘Whirling About Regulator’, another literal translation from the French ‘Régulateur à Tourbillon’, meaning ‘whirlwind’. The now famous tourbillon mechanism is still considered one of the greatest technical achievements in watchmaking.

Breguet’s Influence on George Daniels

“Mechanisms of this type are rare and expensive to make. They are extremely delicate and difficult to adjust for satisfactory working. Once properly set up they are very reliable and keep close, if somewhat noisy, time.”

George Daniels talking about the tourbillon movement in 1974

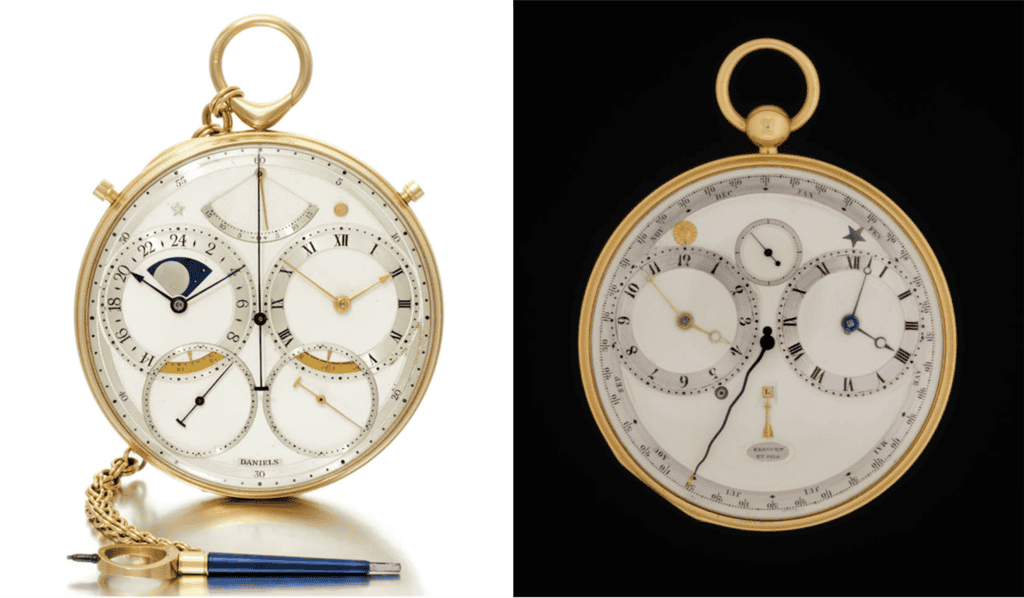

George Daniels was inspired by the work of Abraham-Louis Breguet. This manifests itself in the book The Art of Breguet, which is the complete, illustrated history of the work of Breguet, originally published in 1975. Daniels’ ‘Masterpiece’, the extraordinary ‘Space Traveller’ pocket watch (c.1982) has much in common with Breguet No. 2589 in appearance. Daniels named his creation in honour of the American landing on the moon which was the greatest space journey of the century. It was an 18K gold chronograph with Daniels Independent Double-Wheel Escapement, Mean-Solar and Sidereal Time, Age & Phase of the Moon and Equation of Time Indications.

A Lasting Legacy

The tourbillon is a legacy, alongside Breguet’s many other innovations, that can still be found in modern wristwatches today. Breguet’s genius in design and mechanical innovation must really be seen to be fully appreciated.

This display of timepieces by Abraham-Louis Breguet is at the Clockmakers’ Museum, housed at the Science Museum in London until 8 September. The display showcases extraordinary objects from public and private horological collections. It has been created to mark the bicentenary of Breguet’s death on 17 September 1823, and brings together a selection of his remarkable pieces, united by their connection to England.

The next feature in the series is titled Clocks, Watches and Emperors – The Growing Global Trade of Watch and Clockmaking and is available on Worn & Wound.